This week, delegates from 195 countries are coming together in Paris to discuss a global approach to tackling climate change. It’s the 21st meeting of the Conference of the Parties (or COP) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and after the disappointingly scant results of previous meetings, this time there are some more encouraging signs.

Good COP, bad COP

The appalling attacks in Paris mean that the conference will proceed without the usual pressure of lively protests from those seeking more rapid action. Nevertheless, it is expected that for the first time all countries involved will come forward with emissions reduction commitments intended to keep global warming below 2oC; in fact, 180 have already done so.

In the past, the principal stumbling block to solid commitments has been the objections of the big polluters, despite appeals from the countries first in line to suffer the impacts of climate change. Now China, and perhaps even more critically the USA, appears to be more willing to set aside self-serving scepticism about human beings’ impacts on the planet, and have signalled that they may be ready to embrace change.

You can’t say it’s not much COP… The great and good gather for the Paris conference. Photo: UNFCCC (CC BY 2.0), via Flickr.

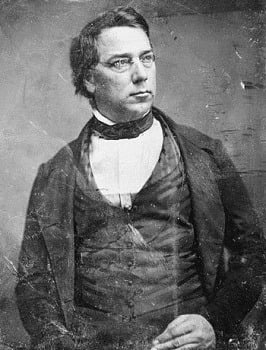

The track record of US intransigence would have been galling to one of the country’s neglected 19th century thinkers. George Perkins Marsh is considered by many to be the first environmentalist and the originator of the concept of sustainability. While pursuing careers as a lawyer, sheep farmer, politician and a diplomat, Marsh somehow also found time to undertake a thorough review of the negative impact people can have on their environment – and what could be done to remedy it.

Back woods man

His book Man and Nature, published in 1864, examined the evidence across a broad sweep of history that deforestation leads to environmental degradation and desertification. He argued that environmental degradation was a key factor in the decline of ancient Mediterranean civilizations, and argued vigorously that we should live in greater harmony with nature.

“The destruction of the woods, then, was man’s first physical conquest, his first violation of the harmonies of inanimate nature.”

Many of Marsh’s observations were surprising at the time, as he traced changes and impacts that would have taken many lifetimes to be felt. Now, some of them are so well established as to become almost truisms. He notes that felling woodland is associated with changes in local temperature, rainfall and the quality of the soil. He connects deforestation with an increase in surface run off and flooding. He also speaks about the harmful practice of slash and burn deforestation and farming – short term gains in soil fertility are quickly diminished, and before long the land is left barren.

Encouragingly for Paris delegates, Marsh also looked at the evidence that mitigation efforts could be successful. He gives several examples of where re-forestation reduced flooding and re-stabilised water sources. He even examined the business benefits from mitigation efforts, citing examples of factories affected by seasonal flooding that had been able to open all year and reduce the costs of repairing flood damage.

Knock on wood effects

Marsh concludes that forests:

“serve as equalisers of temperature and humidity, and it is highly probable that, in analogy with most other works and workings of nature, they, at certain or uncertain periods restore the equilibrium which, whether as lifeless masses or as living organisms, they may have temporarily disturbed. When, therefore, man destroyed these natural harmonisers of climatic discords, he sacrificed an important conservative power.”

Marsh explained that few people noticed the effects of deforestation because they were gradual, and affected different regions in different ways; and that those not yet affected are reluctant to act until it is too late. The parallels with climate change are painfully obvious, particularly when listening to the opening speeches at the COP21 from representatives of the Pacific Island States. They are already feeling the impacts, and now believe we may have left it too late to save their territories from the rising waters.

George Perkins Marsh: Could his ideas help slay the dragon of climate change? Photo: Mathew Brady (Public domain), via Wikimedia Commons.

The President of Kiribati, Anote Tong, thanked Fiji for its offer to accommodate his people if, as expected, climate change renders their island uninhabitable within a matter of decades. I’m sure Marsh would be urging delegates to take careful note of the plight of Kiribati and consider the impact of sea level change on their own populations.

Prince Charles also echoed Marsh when, speaking at COP21, he urged companies to ensure their supply chains are not leading to deforestation. Preventing the destruction and degradation of forests is a key part of tackling climate change, as the UN estimates the loss of around 12 million hectares a year is responsible for around 11% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Indonesia to be wise after the event

Leaders from 20 countries, including the UK and nations with large forests such as Brazil and Indonesia, have used the opportunity of the COP to publish a joint statement recognising the essential role forests play in protecting the planet and avoiding climate change. Needless to say, this must be backed up with action, as the current rate of forest decline is enough to have George Perkins Marsh turning in his grave.

Indonesia is currently suffering from a major air pollution crisis caused by illegal slash and burn clearing methods. Carbon monoxide levels have been close to reaching 2,000 on the Pollutants Standards Index; anything above 300 is considered hazardous. The fires have been so extensive that their CO2 equivalent emissions have exceeded the annual emissions of the UK and Germany. Not only is this swiftly and irrecoverably changing the landscape of Indonesia in favour of short term palm oil and paper profits, but it is also having a major effect on people’s health, with over half a million people being treated for related respiratory infections.

The Indonesian government placed a moratorium on clearances in 43m hectares of forest and peatlands in 2011, but still 30% of detected fires occur in the protected areas and satellite information shows corporations are still slashing and burning. Firm legal action is needed to incentivise people to move away from cheap and polluting practices, and the COP has a critical role in getting governments to agree to the more stringent measures that are required emissions are to be reduced.

Marsh wrote:

“The destructive agency of man becomes more and more energetic and unsparing as he advances in civilisation until the impoverishment, with which his exhaustion of the natural resources of the soul is threatening him, at last awakens him to the necessity of preserving what is left, if not of restoring what has been wantonly wasted”.

Since Marsh died in 1882, our “destructive agency” has become more “energetic and unsparing” than he could ever have imagined. However, the challenges being addressed by COP21 delegates – to overcome short term interests in order to protect the habitability of our planet in the long term – are a direct parallel with those analysed by Marsh in Man and Nature. Those looking for inspiration regarding the necessity for, and possibility of, change could do worse than revisit his writing. Let’s hope that after COP21 we can at last say that we have awakened to the necessity of taking action to avoid disastrous climate change.

Excellent article and much food for thought. Yet again shows that many of our problems and solutions are old concepts repackaged in new terminology. Truisms, as you say.