Local authorities increasingly recognise that how we use urban space can be a key tool in tackling environmental challenges. Most of those that have adopted net zero targets will have considered the contributions made by urban green spaces, or Green Infrastructure (GI) such as trees, parks and green walls or roofs.

Urban food growing however, has received less attention, despite its substantial benefits as a GI strategy. According to Sustain, 59% of councils in the UK have not included food growing in their climate action plans, despite many also having food strategies. In this blog I outline why urban food growing should be a valuable component of any council’s net zero policy.

Pick your own benefits

Community gardens and farms, allotments and private gardens all offer a variety of ‘ecosystem services’, which means that they provide us with direct and indirect benefits. As well as yielding food, growing spaces help regulate heat and water flow, while also providing health, wellbeing and leisure benefits.

Perhaps the most conspicuous of these is the production of local, healthy, often organic, food. The UK imports nearly half the food it consumes and WRAP estimates that the emissions of the whole UK food system in 2019 were equivalent to 35% of UK terrestrial emissions. Urban food growing has lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than shop-bought food because of avoided emissions from transport, distribution and retail.

This general point is illustrated by a life cycle assessment study of a community farm in the London Borough of Sutton, which found that all food commodities supplied by the farm (except polytunnel strawberries) had lower associated GHG emissions than the equivalent in the mainstream food system. The study estimated that the farm could reduce GHG emissions in Sutton by up to 34 tonnes of CO2e per hectare per year. This is much greater than the benefit provided by other urban green spaces such as parks.

As green growing spaces, community gardens are also sites of carbon sequestration. In a 2021 study of soil samples from 200 allotments in 10 urban areas across England, Scotland and Wales, soil organic carbon concentrations in allotments were found to be 250% higher than on conventional arable and horticultural land. The same study reported that, while allotments cover only 0.0006% of Great Britain, they contribute an estimated 0.05-0.14% of total nationwide organic carbon stocks – a disproportionately large contribution.

While the urban cooling and sustainable drainage benefits of urban farms and community gardens are widely recognised, arguably the greatest value in urban food growing, particularly community gardens, lies in education and awareness raising around the environmental impact of conventional food and the potential for local growing to reduce it. As Steve Sayer, CEO of Windmill Hill City Farm in Bristol, put it:

“If you can persuade people that flying strawberries from California for Christmas isn’t the best idea, that’s probably where the benefits for urban growing come… You’re never going to convince everybody; all you’re doing is pushing that bell-curve a little bit one way to get more people aware of seasonality.”

Bath City Farm has further reduced its carbon footprint by using solar energy and an air source heat pump to heat their buildings and provide hot water. Brendan Wistreich, manager at Bath City Farm, told me:

“We have no gas on our site, so it’s a good opportunity for us to talk about the technology that we’ve been able to implement on the farm. Further down the line we could look at having a large-scale ground source heat pump project which could also provide local homes with energy.”

While the carbon savings of produce from urban farms may be modest, combining this with the other opportunities spaces such as community farms and gardens offer makes them a key component in planning for a low-carbon urban future.

Putting the bee into biodiver-city

The 2019 State of Nature Report found that of c.700 bird, mammal, butterfly and moth species in the UK, 41% have reduced in abundance. Underlying this is a decline in the habitats that support biodiversity. For example, according to Natural England, over 97% of wildflower meadows in the UK have been lost since the 1930s.

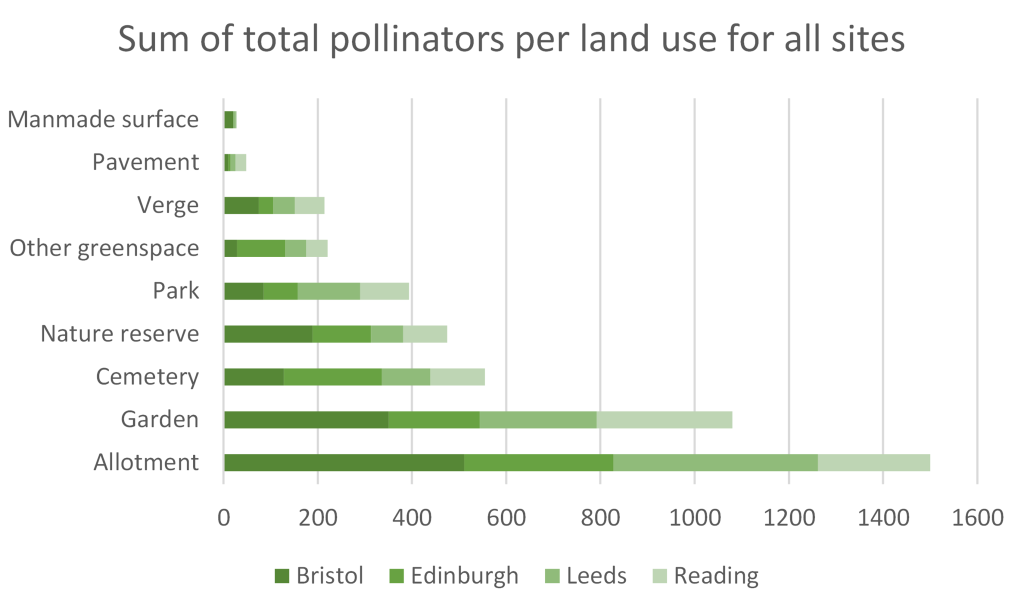

Food growing spaces provide opportunities to create biodiverse and nature-rich habitats in cities. The graph below, taken from a 2019 study of pollinators in four UK cities, shows that allotments (community gardens) and residential gardens are pollinator hotspots.

Mean bee abundances for instance, were found to be between four and 52 times higher in allotments and gardens than for other urban green spaces. At Bath City Farm, over 1,100 species have been mapped and logged by local ecologist and Farm trustee Mike Williams, with the team working towards enhancing biodiversity even further. As Brendan Wistreich explains,

“We’ve got a plan for how we’re going to develop the site for conservation using rotational grazing to regenerate grassland habitats. To bring back wildflowers we’re creating a traditionally managed hay meadow, a 60m bee and butterfly bank and a wildflower nursery. Small urban farms can balance nature restoration alongside the production of food as co-dependent systems.”

As the pressures of industrial agriculture and urbanisation intensify, creating space for nature and connecting people to it is increasingly vital. Gardens and allotments have a small but important role to play: the data suggests that, as currently managed, they support biodiversity more than other urban green spaces such as parks and verges, and that there is scope for them to be managed so as to increase biodiversity benefits still further.

Chasing ‘The Good Life’

The benefits of urban food growing space require labour to achieve – but fortunately there is no shortage of those willing to get their hands dirty. Indeed, a 2022 survey found that almost 87% of local authorities in the UK have reported an increase in demand for allotments since the pandemic. Most have waiting lists, with some people reportedly waiting as long as 17 years. But despite demand, between the 1950s and 2020, there has been a 65% reduction in allotment land in the UK.

It would seem that making new land available for allotments and other community food growing spaces would be a useful element to include in a local authority’s GI strategy, but according to Ruth Westcott of Sustain, councils struggle to protect or find new spaces for community food growing due to competition for space from developers. “Part of this,” Ruth reported, “is because councils don’t appreciate the value of food production to their net zero strategies.”

While the Scottish Government requires councils to create food growing strategies, there’s no equivalent obligation on English authorities. And while providing allotments is a statutory obligation for councils, that doesn’t extend to other community growing spaces. Westcott suggests that including community food growing spaces within the statutory definition of an allotment would help motivate councils to make more land available.

There are some positive English examples of food production being taken into consideration in planning. Kensington and Chelsea Council requires new developments to reduce carbon emissions, including through provision of on-site food production, and since Brighton and Hove City Council introduced a planning advisory note encouraging new developments to incorporate food growing space, over a third of approved planning applications have done so.

Meanwhile, draft policies proposed in Bristol City Council’s 2022 Local Plan Review set out requirements for new large developments to provide allotment space to residents as ‘valuable community and green infrastructure assets’. Specifically, residential developments creating 60 dwellings or more will be expected to provide one statutory allotment plot either on or off-site, and all new residential developments will be expected to provide space for on-site food growing by residents, such as communal or rooftop gardens, raised beds, orchards and hedgerows.

Clearly there remains more that could be done to provide growing space in cities. Adequate funding is needed to protect current, and create new, food growing spaces, coupled with a policy framework which requires such spaces to be part of any future development. Crucially, national and local planning policy should recognise community and private food growing as a valuable type of GI which can not only contribute to climate and nature objectives, but can also bring significant positive health and wellbeing impacts.

Featured image: Patrick Federi via Unsplash

Leave A Comment