Last week’s announcement by Defra that it was withdrawing around a combined £200 million of PFI funding from three waste projects (Merseyside, Bradford / Calderdale, City of York / North Yorkshire) was met with some anger and derision across the waste industry. No surprises that the loudest voices were those who have invested significant amounts in these projects, not least the successful bidders (or ‘nearly successful’ in the case of Merseyside) in each related procurement.

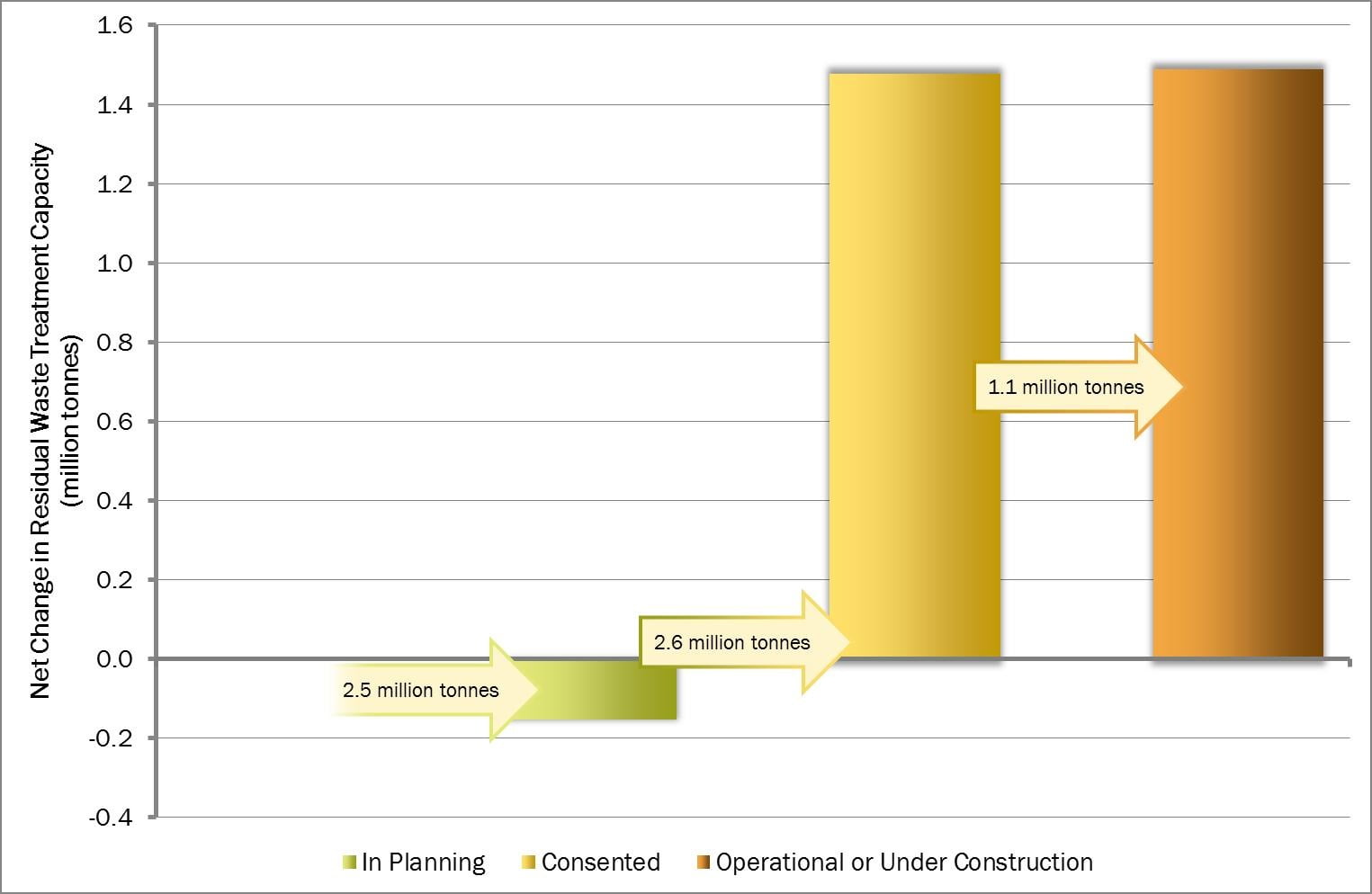

It was reported in the press that Eunomia’s Residual Waste Infrastructure Review, of which I am lead author, influenced Defra’s decision-making. At the same time, I was quoted, correctly in terms of the wording, but somewhat out of context, stating that there is five million tonnes more consented treatment capacity than there is residual waste.

Whilst Defra might have taken note of the findings of our report, their prime motivation is to meet the EU Landfill Directive targets at minimum cost, and they have taken the view that they can’t justify paying out this vast sum of money when it is not required to meet the national target.

Not so fast

The issue of potential ‘overcapacity’, which previous versions of our report have highlighted, is a separate one. Whilst the third issue of our report, published in November of last year, does demonstrate that we are heading in that direction, there are a number of factors, aside from Defra’s withdrawal of PFI funding, which are currently resulting in projects not moving forward as quickly as they might. These can be summarised as follows:

- Lack of attractiveness of local authority projects – the current limited availability and cost of lending is such that even the large waste management companies are struggling to raise finance at attractive terms. Last month Sita pulled out of the North Wales incinerator procurement, whilst in January Veolia withdrew from the North London residual waste tender. Both procurements were down to just two remaining bidders, and the late withdrawals have thrown them into doubt. The UK Green Investment Bank (UKGIB) is attempting to plug the lending gap for such projects, but has only limited funds with which to do so;

- Difficulty of financing merchant projects – the UKGIB has recently confirmed what was suspected, that it is not willing to lend to merchant projects, which do not have a long-term guaranteed feedstock contract. In a tough borrowing environment, therefore, reaching financial close for such projects remains a considerable challenge;

- The option of exporting SRF has become a credible, medium and long-term option for both local authorities and the commercial sector. Whilst organisations with treatment infrastructure in other EU Member States now represent a major threat to the success of local authority procurement processes, their effect is particularly strong on merchant facilities. Although there is finite spare capacity in Germany and the Netherlands, for example, this is having an disproportionate impact on proposed plant in the UK. Because the ‘export threat’ is not limited by geography, the spare capacity that exists can be counted against every single UK project under development and impact on the prospects of each gaining finance. Only when the spare capacity is filled will this threat recede.

In the November 2012 issue of our report, the Eunomia team responsible for the Infrastructure Review therefore ran an additional ‘time delay’ scenario, to take the above factors into consideration. This scenario again showed a situation of overcapacity, but around two years later than previously forecast.

In the development of the fourth edition of the report, which will be published in May 2013, we will again take stock of the financing situation. In the event that our assessment is that changes are needed to the assumptions underpinning our analysis we will of course make them. The methodology and related assumptions are set out very clearly in our report; it is my feeling that analysis of the sort it provides is only of value if it is fully transparent about how it is carried out.

Age of consent

Because we have now published three versions of our study, we are able to show a trend analysis, also included in the high-level version of our study that we make freely available. The report is therefore able to show a developing picture of the speed at which facilities are moving through the consenting process towards commissioning and ultimately becoming operational. This is essential information in order to reach a national policy view regarding the current position.

As a result, in the third issue of the report, we were able to show that contrary to industry perception, residual treatment capacity is receiving planning consent quickly, with capacity being consented faster than new applications are being made. Over the six month period to November 2012, 2.6 million tonnes of capacity were granted planning consent and an additional 1.1 million tonnes of treatment capacity came on stream. It has therefore been a surprise to me that other industry commentators still bang on about planning being the major barrier to capacity development.

Unlike many of our competitors, Eunomia does not (currently!) provide extensive planning and permitting services for large residual waste infrastructure projects in the UK. I therefore feel that we can provide impartial market analysis in this sphere without being influenced by our clients’ wider objectives. Our database is comprehensive, including every waste treatment facility in the whole of the UK. I will always make sure that corrections are implemented whenever gaps are pointed out to us, but the last time we needed to do this was November 2011. For developers, this allows us to provide accurate investment advice to minimise the risk of stranded assets.

The UK needs sufficient infrastructure to treat our residual waste and divert it from landfill, and the current financing environment is making it more difficult for facilities with planning consent to move to financial close. However, there remains a real risk of excess capacity, which adds to the difficulty of obtaining investment. We already see this in various northern European countries which have over-invested in treatment facilities and which are now seeking to import wastes from the UK to fill them.

Leave A Comment