8 minute read

Can you remember when you last experienced a power cut in the UK? Thankfully, groping for the emergency candles is a short-lived novelty rather than a day-to-day worry: the National Grid’s 2013/14 performance report confirms that the annual total unsupplied electricity for England and Wales was just 135.9 MWh – a reliability rate of 99.99995%.

Maintaining this high standard of reliability is the goal of the UK’s first Capacity Market (CM) auction, whose results were published on 2nd January 2015, leaving energy suppliers with an apparent annual bill of nearly £1bn. But why is it needed, and what has the money delivered? Will consumers be left bearing the cost? And has the scheme made energy supplies more secure?

Carbon dated

The assumption that UK power supply infrastructure can readily respond to electricity demand is becoming a casualty of the drive to decarbonise. Coal and gas-fired power stations are reasonably responsive – it takes around four hours for a coal plant to reach full output capacity, while gas can be on stream in an hour or less. Low carbon generation, though, means relying on intermittent or inflexible sources such as wind and nuclear.

Meanwhile, the economics of coal and gas are becoming less favourable. Low carbon power generation technologies are costly to build, but once operational produce power far more cheaply than conventional generation. High marginal costs mean that some older, less efficient gas plant is now used for just 10-15% of the year, mostly during high demand periods in the winter months. The price differential is augmented by the UK Carbon Price Floor scheme, which tops up the EU Emissions Trading System by fixing a ‘floor price’ for carbon emissions. Over recent years, EU ETS credits have traded at between €5-7 per tonne; the ‘top-up’ has been around £6 per tonne, and was capped by the Treasury in March 2014 at a maximum of £18 per tonne until 2020. Thereafter it is set to rise to £32 per tonne.

The CM is something of a life support system for conventional generators, and much of the flak it has attracted since being announced in 2012 has focussed on the eligibility of polluting coal and gas power plants for payments. Most coal and gas plants are set to close by 2030, but the CM ensures they remain available if needed. Participants guarantee that their plants will be running when the grid is short on power in exchange for a payment based on the amount of capacity they will contribute.

The payments are set through annual ‘pay-as-clear’ auctions, for the most part held four years in advance of when the contracts take effect. Contracts are awarded to the lowest priced bids first, continuing up the price scale until the required generating capacity is reached. All successful bids then receive the price of the highest accepted bid: £19.60kW/year for the 49.26GW secured for 2017/18.

Pennsylvania or bust?

The ‘cost’ is shared between energy suppliers in proportion to the amount of power that each supplies. However, if the electricity market is effective, the additional cost should be far less than the widely quoted £1bn. Electricity generators should use the additional revenue to reduce their consumer electricity prices, resulting in zero net impact on suppliers and consumers. Indeed, DECC’s 2014 impact assessment of the CM suggested it would increase energy intensive industries’ bills by no more than 3%, while domestic consumers were forecast to see prices fall by 2026.

All the CM should do then, is offer a greater share of the pie to providers of generating capacity, instead of paying only for the energy that is generated. But will it really work this way?

The best comparator is Pennsylvania’s Reliability Pricing Model (RPM) Capacity Market. Introduced in 2007, it has served as a blueprint for the UK system. The influence of the RPM on Pennsylvania’s power prices is difficult to pinpoint, but they are not appreciably lower than elsewhere in the US. Regulators have suggested that anti-gaming mechanisms may be required to avoid over-compensating generators. Such concerns are hardly reassuring for UK electricity consumers, and transparency in the generation and supply markets will become more important than ever to ensure confidence.

Encouraging reaction

Coal and gas generation weren’t the only controversial inclusions in the auction. DECC’s early policy publications highlighted the inflexibility of nuclear generation within the grid as one of the threats to security of supply. When the UK’s existing nuclear fleet was allowed to participate in the auction it came as a surprising reversal, announced just six months before bidding was due to start.

Nuclear power plants take days to ‘ramp’ up and down and play no role in matching electricity generation with variations in demand. I suspect that the late U-turn was prompted by concerns that if the CM did not treat all technologies equally it might fall foul of EU State Aid rules, which could have derailed the entire Energy Market Reform (EMR) program.

Will there be a crock of gold for those who offer capacity? Photo by Andy Stephenson via Wikimedia Commons

The result is a windfall of more than £150m for EDF, which owns eight of the UK’s nine remaining nuclear plants. EDF had already announced life extensions for all but two of these, keeping them in service beyond 2020. It’s perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that EDF has since announced a ten year life extension for the 1090MW Dungeness B plant.

Fortunately, nuclear power forms too small a part of the CM to negatively affect reliability of supply, although it has absorbed money that might otherwise have encouraged the development of new flexible generation facilities. That said, it is likely that some nuclear plant would otherwise have closed down, so the CM has probably reduced carbon emissions by delaying or preventing the need for new gas fired plant.

Having an off day

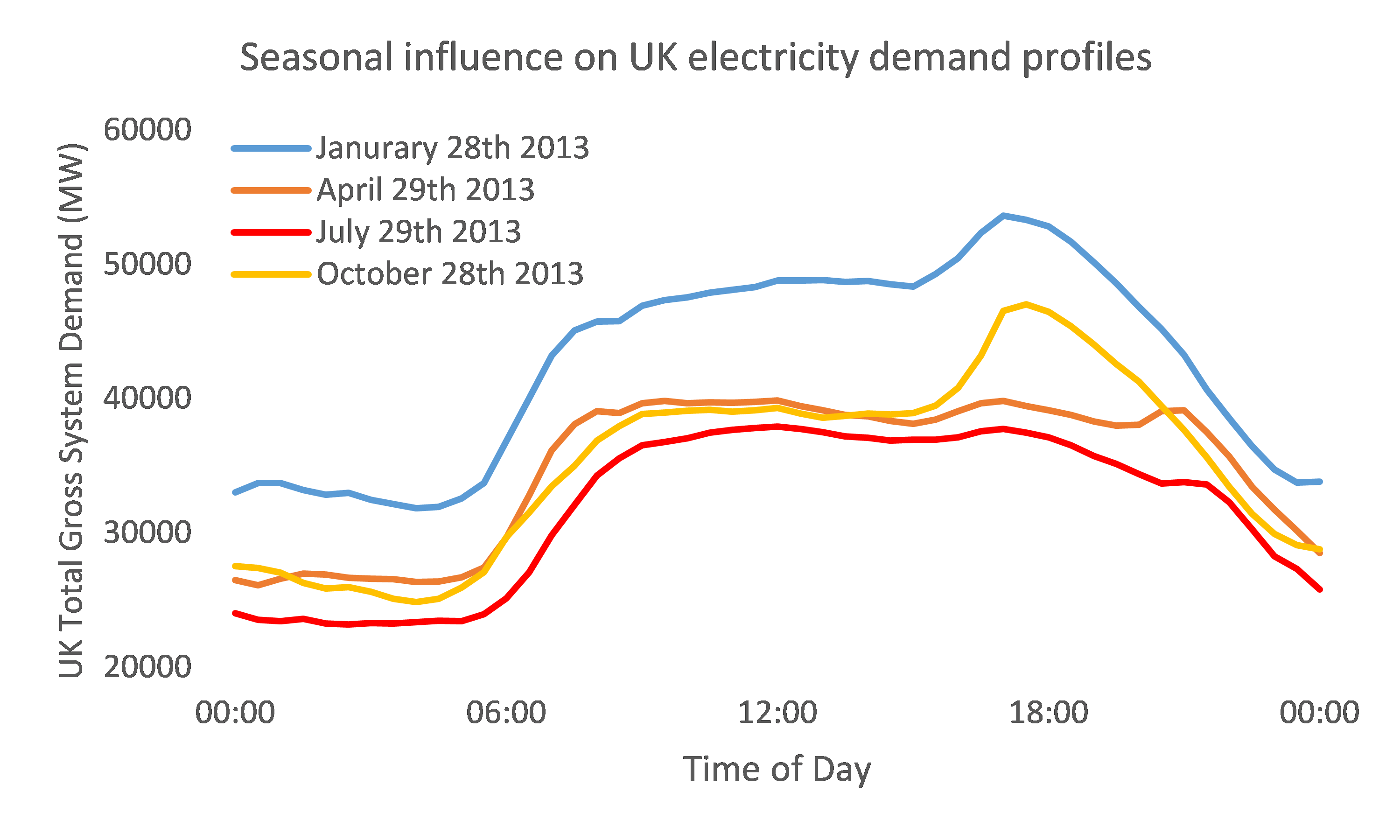

Electricity demand within the UK varies seasonally and through the day. When energy industry stakeholders talk about ‘keeping the lights on’, they are really referring to being able to meet winter peak demand. Achieving this will be the main measure of the CM’s success.

The chart below shows UK electricity demand for the last Monday of four months in 2013. Demand is higher in winter than in summer and we use more power in the day time than at night. A chilly and windless winter afternoon is a perfect storm for the National Grid, and a significant amount of generating capacity exists solely to cover such eventualities, which occur only a few times a year.

Rather than supplying more electricity to deal with times of system stress, consumers can be paid to cut back their use. The Pennsylvania capacity market currently employs 9.9GW of ‘demand side’ response (DSR), equivalent to 6.3% of peak demand. In 2012, Ofgem estimated DSR could reduce UK winter peak demand by 4.4GW, or around 8%.

However, just 174MW of DSR – 0.3% of peak demand – was successful in the UK CM auction, and some of that was from Aylesford Newsprint, which is now in administration. The failure to attract competitive DSR bids raises concerns, both regarding the auction process and the ability of the EMR to cost-efficiently decarbonise the UK’s electricity system.

Dealing with the competition

A competitive auction is essential to keep prices down, but unsuccessful bidders in the recent process may realise that they will also struggle to compete in the future. Some may choose to permanently close plants rather than incur the cost of maintaining them in the hope of future contracts. Less competition from plant could give DSR a more prominent role in future auctions, but it could also give large generation portfolio owners more market power and lead to higher clearing prices.

DSR providers could be encouraged to take up the slack by allowing them to bid for the 15 year contracts available to new build generation. DECC’s decision to limit DSR to one year contracts, which offer little incentive for investment, is being challenged in the European Court of Justice. Better forecasting of when and how often CM warnings will occur would also help DSR providers by making it clearer how much any failures to respond might cost them.

2.6GW of new build was successful in the auction, of which 1.65GW is attributable to Carlton Power’s Trafford Power Station, a prospective CCGT plant. Carlton’s confidence in the economics of gas is remarkable. Prior to the auction, many commentators doubted whether new CCGT capacity would be viable even if the auction reached its administratively capped price of £75/kW. Carrington Power Station, another CCGT in Manchester, didn’t make the cut despite already being under construction. If Trafford were to pull out, the resulting shortfall would mean the CM would fall short of ensuring that 2017/18 winter peak demand could be met, and DECC would be scrabbling to plug the gap at the T-1 auction in 2016/17. With a shorter lead time there may be less competition, and thus higher prices.

While the overall price tag of the first CM was lower than expected, there are clear reasons to be concerned over how the money is being spent and whether it has fully achieved its goals. DECC may need to make some modifications if future auctions are to succeed in keeping the lights on at a price consumers will accept.

Well surprise surprise, we get power cuts in Buckinghamshire roughly twice a montha and they range from a few minutes to over an hour although they have been as long as 8 hours during last year, and two years ago 18 hours. These are regular occurrences and very annoying. And when questioned they supply glib answers about dealing with the issues.