What does the UK need if it is to meet its Carbon Budget commitment to reducing carbon emissions? Perhaps the first thing you might think of is reducing the amount of energy we use, by improving the energy efficiency of our homes and businesses. Or you might think of the need for more generation capacity for renewable energy, perhaps wind farms or solar panels. But a critical and often under-appreciated constraint is the vital infrastructure that underpins the whole system: our electricity network.

The move away from centralised power generation to more small-scale and more intermittent, energy generation in the form of renewables, means significant changes and challenges in the way electricity is managed. It is therefore vital that the system is managed effectively to ensure grid constraints do not lead to negative impacts. The government is certainly aware of the need to update our electricity infrastructure, but it is less clear that it is talking to the right people or planning the right steps to prepare the national grid for the demands it will have to meet.

Electric switch

It’s important to understand why the ongoing radical change in how the UK generates its electricity has a bearing on the electricity network. We have long had a range of energy sources, including coal, gas and nuclear. Some plant act as baseload and some can be more readily switched off and on; but all have followed the same centralised model, with electricity produced at large power stations and transported across the country to wherever it is required. The network we have built is, understandably enough, designed to support this style of generation.

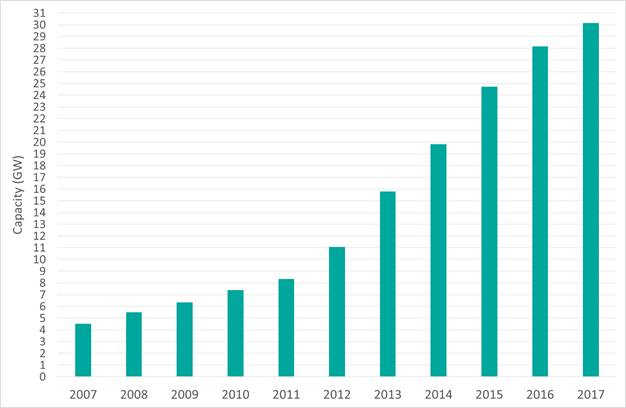

Over the last ten years the UK has seen a major shift towards renewables, with the electricity sourced from renewables increasing from around 20 TWh in 2007 to over 80 TWh in 2016, when it accounted for almost 25% of all electricity used in the UK. Eunomia tracks the planning and deployment of renewables through its work on the government’s Renewable Energy Planning Database (REPD) – the source for the chart below, which shows the increasing peak capacity of UK renewable generation.

Cumulative capacity of operational renewable energy generation in the UK (to June 2017). Source: REPD

There has been a corresponding decline in fossil-fuelled generation; 24 power stations have closed since 2011, while two more have closed in part. The UK government has stated that the last eight coal-fired power stations (representing 21% of electricity generation) will close by 2025. There may be some doubt over their commitment, but the direction of travel is clear – more electricity will be generated from low-carbon sources. To understand the implications this has for the grid, it’s important to understand how electricity is currently managed.

Supply sides

Electricity is transported using two key methods: transmission and distribution. Transmission involves the transport of electricity from large power stations, which can have generation capacities of anything from 500-2000MW, over long distances. To minimise energy lost to resistance, this necessitates a high voltage, from 132-400 kV. Transmission is the responsibility of the System Operator, National Grid in England and Wales, while in Scotland it is shared between SSE and SP Energy Networks. Once electricity arrives at the substation, distribution takes over.

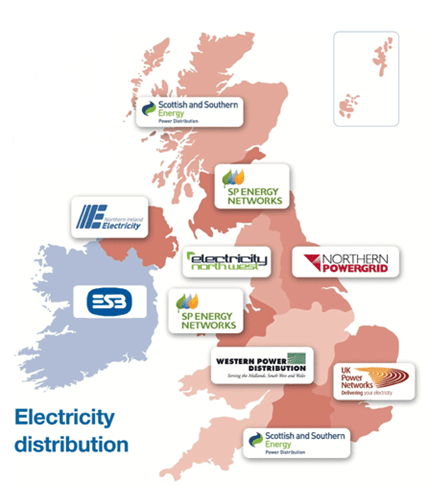

At the substation, the voltage is substantially reduced for local distribution, to between 2 and 35 kV – a level suitable for typical power demand from homes and businesses. Distribution is managed by Distribution Network Operators (DNOs), shown in the map below, which operate on a regional basis. DNOs are monopolies managed by Ofgem and it is they who are ultimately responsible for ensuring electricity reaches your home – not your ‘energy supplier’, be they one of the ‘big six’ such as British Gas or Eon, or a smaller company, like Ovo or Good Energy.

Distribution was designed with this top down model in mind, and only the largest renewable energy generation facilities warrant their own high-voltage transmission cables. Most are less than 50MW, and input their electricity directly into the distribution network. As the share of UK electricity generated by smaller-scale renewables increases, demand on the transmission network is falling, but the distribution network is coming under strain.

DNO test

For DNOs, the relatively simple task of distributing power received from the transmission network has become a thing of the past. Now, they also have to manage inputs from several thousand smaller, widely dispersed, often intermittent renewable energy generation sources. Part of the problem is that the grid was not designed to facilitate the movement of electricity from the distribution to the transmission network, or from one DNO’s area to a neighbour, so it is difficult to send power for use elsewhere – which can lead to electricity being wasted.

DNOs have also had to make large numbers of grid connections available for renewables, which in some parts of the country has been the limiting factor in their deployment. It doesn’t help DNOs that rapid changes in subsidy have increased the difficulty of predicting the demand for new grid connections. Even for me and my colleagues, who speak to developers every month regarding the status of their projects to inform the REPD, it’s hard to accurately assess the likelihood of projects with planning consent being constructed.

Are we at the dawn of a transformed electricity grid? Photo: David Steele (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0), via Flickr.

Overcoming these problems requires ongoing reinforcement of the distribution network: new physical infrastructure, such as cables, and additional management to ensure constant supply, even when the power generated by renewables fluctuates. The additional costs are initially met by the DNOs, but are ultimately paid by consumers through levies on bills, which are regulated by Ofgem through RIIO price controls.

DNOs currently have to make judgement calls on where additional reinforcement for the grid is required, decisions which are predominantly influenced by where there is high demand for connections. Connections are currently offered on a “first come, first served” basis but in future there may be other factors that DNOs need to consider.

Stored up demand

One important change is the rise of electricity storage. Just last month BEIS announced a new strategy to encourage innovation in storage by recognising it as a distinct form of energy generation. Ofgem has also signalled its interest in encouraging storage, proposing changes that could cut 20% from the cost of storage and facilitate bringing 550MW of capacity online. More storage will help DNOs manage increasing quantities of renewable electricity more efficiently, providing grid balancing services and smoothing out peaks and troughs of usage, so there may be a case to prioritise storage projects for connection.

Some DNOs are interested in operating their own storage capacity, but are barred from doing so: storage is classed as a form of generation, and DNOs are not allowed to be generators. Western Power Distribution has decided to become a distribution service operator (DSO) instead, allowing it to offer a wider range of services that could include procurement of storage. UK Power Networks looks set to do likewise in the next year.

Another challenge is a projected increase and change in electricity usage. The switch to hybrid and electric cars means that a large share of the energy demand that is currently met by petrol and diesel will gradually shift to the grid in the coming years – much of it charging overnight. Decarbonising our heat requirements, too, may increase demand for electricity to power technologies such as heat pumps. Other sources of demand, such our growing need for large data centres and addiction to electronic devices, all seem set to entail a significant increase in electricity usage in coming decades.

That implies a need for more renewable energy generation, which must in turn be supported by grid infrastructure. Grid reinforcement takes time: we have previously seen how a lack of grid connections can create a bottleneck – a prominent issue as the industry rushed to complete projects and get them connected before ROC subsidies were axed in March 2017.

Since DNOs cannot respond instantly to sudden policy changes, it is essential that government gives them clarity regarding the types and scale of generation and storage that it believes are required, so that they can plan the necessary reinforcement work. Otherwise, grid limitations may delay and deter developers seeking to bring new projects online.

I’m part of a team working on a Eunomia special report, based on REPD data and our in-house database of energy storage projects. Its aim is to demonstrate the impact of policy on the deployment of renewables, and to examine the conditions that might restore growth to the sector – whether policy measures or market change. By increasing understanding of these issues, we hope to guide policy – and infrastructure investment. If you would like to be notified when it is released, please get in touch.

Leave A Comment