Amid all of the impacts that we are learning Brexit might have, one neglected area is the potential effect on the UK’s renewable energy sector. The general assumption seems to be that, because the UK’s Climate Change Act 2008 (CCA) has set targets that are more stretching and look further ahead than any EU legislation on the topic, Brexit is unlikely to have much impact. But is that a safe assumption on which the solar industry, for example, can proceed?

Solar’s sunrise and sunset

Across the UK, electricity generation from renewables has increased rapidly since the turn of the century. From the early 2000s, wind power began to take off; by 2011, solar panels were being widely deployed on the roofs of residential properties, and large-scale solar installations started to appear. A decade ago it provided virtually nothing; today renewables contribute nearly a third of all electricity generated in the UK.

The initial increase in solar PV installations was largely driven by government support schemes. From 2002, the Renewables Obligation (RO) encouraged investment in larger installations, while the Feed-in Tariff (FiT), which was introduced by the government in April 2010, was available to support small-scale generation. Under the latter scheme, homeowners and businesses received payments for any electricity they generated and didn’t use, but exported back into the grid. As a result, solar panels appeared on roofs of homes across the UK.

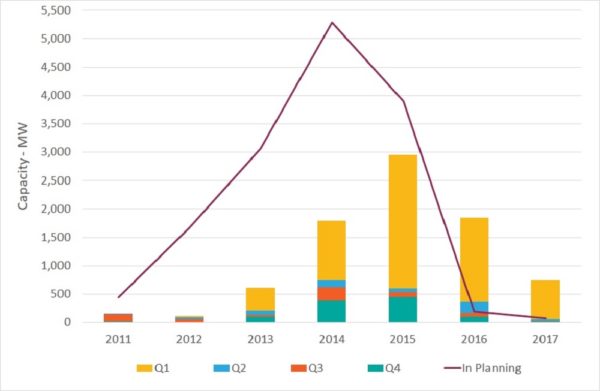

However, since 2015 the UK has restricted and then closed these two key renewable energy subsidy schemes. As a result, solar PV installations have plummeted. In 2016, the first year that these incentives were slashed, small solar installations fell by 74%, compared with the same period the previous year. Meanwhile, the planning pipeline for larger installations dropped even more precipitously.

Solar PV generating capacity (>1MW facilities) deployed and in planning, 2011-17. Source: Renewable Energy Planning Database/Eunomia.

A similar decline has been seen in onshore wind facilities, although this is perhaps driven more by new planning conditions placed on windfarms than by subsidy cuts. Only offshore wind, whose costs have tumbled in recent years, has maintained its rate of deployment, while a small number of new large-scale solar projects are moving ahead where – for a variety of reasons – they are in a position to do so without subsidy.

Domestic-scale installations continue, but at a tiny fraction of the rate they did at the peak of the market. With no system currently in place to pay new small generators for electricity they export to the grid, the government doesn’t seem to see this sector as a priority – perhaps due to the amount of effort being diverted into Brexit preparations.

Targets mean targets

Despite the slowdown in renewables deployment, the UK is on track to reach some of the targets for 2020. The 2018 Committee on Climate Change progress report found that UK emissions are down 43% compared to the 1990 baseline – greater than the reduction needed to meet the carbon budget for 2018-2022 (37%). It also means the UK is doing its share to fulfil the a joint pledge by members of the European Union (EU) to achieve a 40% reduction in emissions by 2030 – again compared with 1990 levels – that was entered into under the Paris Climate Agreement.

However, under the EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED), the UK needs to be producing 15 percent of all energy from renewable sources by 2020. The latest Digest of UK Energy Statistics (DUKES) reported that in 2017, 10.2% of total energy consumption came from renewable sources, including 27.9% of electricity generation; 7.7% of heat; and 4.6% of the energy used in transport. With electricity being the easiest to decarbonise in the short term, there is an urgent need to make further progress over the next couple of years, so long as the UK remains subject to EU law.

Leavers of power

So how will Brexit affect that? In the short term, it is unlikely to make much difference. The reality is that when it comes to renewable electricity installations, long lead-times mean most of the solar PV – and other renewable electricity – projects that are going to be onstream by the time 2020 comes around are either operational or quite far developed, and unlikely to be affected by any future policy changes.

What about the longer term? One worry is that, when (or perhaps “if”) the UK leaves the EU, it will no longer be obliged to meet its RED targets. The government has given various commitments to maintain environmental standards after Brexit, and of course the future carbon budgets under the CCA actually require greater cuts in emissions than anything now in EU law: an 80% reduction from 1990 levels by 2050. Ministers have outlined plans for a new green watchdog to protect the environment after Brexit. This will be an independent statutory body to safeguard environmental standards. It will have the power to take the government to court to enforce environmental law after Brexit.

However, none of this provides guarantees regarding what the content of environmental law will be. The CCA is not set in stone; some of those who back Brexit have previously called for it to be scrapped, and there is nothing to stop a future government from repealing it. Nor would a future government be bound to maintain the standards required by the RED, or adopt more challenging future targets under revisions to the directive. If the economic impacts of Brexit are as dire as some fear, a future government may be under pressure to make a dash for growth, no matter the environmental cost.

The short and simple answer is that nobody knows exactly what effect Brexit will have on the solar industry, or on renewables more widely. There is widespread public support for renewables in general, and solar in particular. Regardless of the outcome of Brexit, it’s important that the government continues to support and take advantage of the huge potential of using solar power as a clean, green source of energy that can contribute to a sustainable future.

Outside the EU, it will be down to the actions of the UK government and devolved administrations to determine whether we take advantage of the opportunities. A renewables-friendly government could easily implement policies that would boost the solar industry (just as it could today). However, the opposite is equally true; and the proposed Environmental Watchdog would not be able to force the hand of a government determined to set aside decades of green policies. In the end, it will be down to each of us to give greater priority to the green credentials of the parties and candidates we vote for if we want to ensure that the transition to renewables continues apace in the UK.

Featured image: jonsowman (CC BY 2.0), via Flickr.

Leave A Comment