by Phillip Ward

5 minute read

Back in February, I wrote a piece describing the mess Defra were getting into with the legal transposition of the Waste Framework Directive. A legal challenge to their first draft regulations had objected to Defra’s attempt to say that co-mingled collections were a form of separate collection and prompted the publication of a revised version for consultation.

My verdict at the time was that they were probably not out of the legal woods since their second attempt included a fairly blatant twisting of the words of the directive – again to preserve co-mingling as a mainstream option. It seems I was right since, just as Parliament was rising for the summer recess, Defra slipped out yet a third version of their regulations complete with warm support from the Local Government Association (LGA) and the Environmental Services Association (ESA) and the confident hope that this would draw a line under the legal challenge. The challengers, who seem to have been caught by surprise, responded with a message that basically said “See you in court”.

Fourth time lucky?

Having three attempts at writing regulations is fairly rare but, if I were a betting man, I might make a punt on them needing a fourth set before they are through. So why are they struggling so much? On the one hand they have the EU Commission and the European Parliament concerned about coming resource constraints; sitting on evidence from other member states that separate collections work and produce quality materials capable of being used by local reprocessors. They are backed in this by manufacturers who are finding it hard to secure materials and reprocessors who cannot secure enough feedstock of a quality they can use, without further cleaning.

On the other hand, Defra faces domestic political pressures. They believe that co-mingled collections are more popular with the public, and may be right about this; especially where household space is tight and managing multiple containers can be a problem. They also believe that co-mingled collections are more effective at increasing recycling rates. I disagree, but that’s an argument for another article.

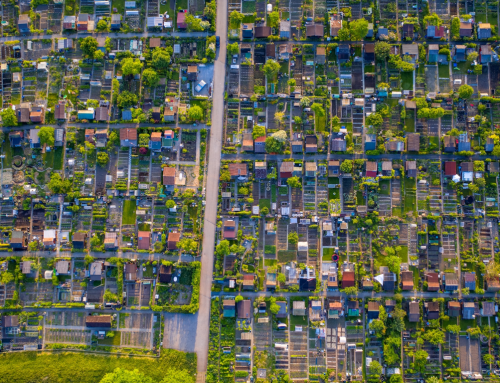

Can a simple split between waste and recycling survive? Picture by Lisa Jarvis, via Wikimedia Commons

The ESA is keen to preserve co-mingling: some of its members have invested heavily in sorting equipment and MRFs; others make their money through lightly regulated waste exports to markets that are willing to take indifferent, contaminated material. To put it bluntly, if you can get away with selling to China a container nominally full of plastic bottles but including a good measure of rubbish, not only do you save money compared with sorting it properly; you also get a premium price for your rubbish, and avoid the cost of landfilling it. I don’t want to impute bad motives to individuals or the waste industry as a whole. I know there are many working hard to improve the technology and quality standards. It’s just that I think they are trying to make a silk purse from a sow’s ear.

The LGA, too, are keen to preserve the co-mingling option. This is partly because they don’t like being told how to do things – localism. It is also partly because they agree with Defra that it is more attractive to some residents/voters and partly because they are rightly terrified of the cost of being forced to change systems on a short timescale, which could break some pretty tight budgets.

Leadership challenge

Defra are in a difficult place – even if it is of their own making. They thought they had a deal with the European Commission. When they signed up to the revised Waste Framework Directive, they entered a minutes statement clarifying that they understood co-mingling for later separation to be the same as separate collection. It now seems that the Commission’s concession was limited to accepting a “proportionality” test so that co-mingling is accepted where separate collections are disproportionately expensive or difficult – and then only if the same quality of materials is achieved.

Defra’s real problem is that they – including Ministers – are acting like bureaucrats when the situation needs leadership. If they believe any of their rhetoric about zero waste to landfill, they have to mean zero waste to landfill anywhere, not just in the UK. If they believe their rhetoric about a resource industry not a waste industry, they have start shifting practices so that the material which comes back after use is in a fit state to be used again in a high value application, whether here or abroad. And somehow they have to find a way of recovering the time that has been lost pfaffing around with transposing the directive to give everyone time to plan for the transition.

I think that means Defra has to settle the court case, if they can. I’m not sure how they could do that, because I don’t know what the complainants will settle for after being messed about for so long. But one option would be a fourth set of regulations making a literal transposition of the directive, without the lawerly tricks we have seen so far, coupled with a serious attempt to drive up quality from all MRFs and effective regulation of exports.

Defra needs to give clear signals that we are moving towards separate collections to allow local authorities to reflect this in contract renewals as they become due. Some serious effort needs to be put into solving the practical problems of managing multiple waste containers in small properties and to investigating different configurations for MRFs so that they sort what can’t be separated at the kerbside – different plastics, and metals for example.

That would not necessarily satisfy the EU Commission, but I think they would be more inclined to give us breathing space if we had established a domestic agreement and were rowing with the tide rather than against it.

Leave A Comment