by Steve Watson

7 minute read

While we may never know for sure if there is life after death, we can be sure that there will be environmental impacts. If it weren’t bad enough that we spend our lives consuming natural resources and steadily accruing huge carbon footprints, thanatophobic environmentalists may add fears of ongoing emissions and land use to the other horrors of the grave.

Yet, as we all must face our own mortality, we should also face the fact that something will need to be done with our mortal remains once the soul has flown its biological nest. For the environmentally minded, it would certainly be helpful to understand the most pressing issues and sustainable options.

After-lifecycle analysis

Perhaps partly because of a general aversion to thinking too much about death, there isn’t a great wealth of scientific data on the environmental impacts of funerary practices. One valiant attempt to analyse the myriad elements which make up one’s final rites has been made, however, by the Centre for Energy and Environmental Studies at the University of Groningen, which provides a life cycle analysis (LCA) of four different funerary practices in the Netherlands.

Data provided by the Dutch funeral industry was used to compare the relative environmental impacts of burial, cremation, and two new technologies.

- ‘Resomation’ is a kind of alkali hydrolysis in which the body is heated under high pressure in a mixture of water and a caustic compound, breaking it down into its chemical components.

- Cryomation involves freezing the body with liquid nitrogen before disintegrating it into small particles by means of vibration, which are then further freeze dried to reduce their weight.

The study applied three LCA methodologies: a damage-oriented method, a monetised costs method, and a combination of the two. On all three analyses, burial had the highest environmental impacts, followed by cremation. In the combined LCA, burial was shown to result in the greatest fossil depletion, ecosystem damage, particulate matter formation, toxicity, climate change related damage to human health, and urban land occupation. Cremation had about one third of the total impacts of burial, due to reduced values in all these areas.

Are funerary practices on an environmentally responsible path? Photograph by Myrabella (CC BY-SA 4.0), via Wikimedia Commons.

Meanwhile, cryomation and resomation came out looking quite good, having around one seventh and one ninth of the impacts of burial respectively. They also produce some positive benefits in terms of material recovery: valuable metals are preserved in the process, for example from medical implants. However, caution is needed because the novelty of these technologies means there is little independent data on them, leaving the studies reliant on environmental information supplied by the companies behind these new methods.

Interestingly, the study also looked at the impacts associated with many aspects of the farewell ceremony not directly linked to the deceased’s final environmental reckoning. This includes preparing and laying out the body, corresponding with friends and relatives and getting them to the service, and providing food and drink for the wake. These other funerary aspects were found to have a much greater impact than even burial, the greatest contributor being fossil depletion from transport.

A grave matter

The Groningen study also compares the environmental impacts of funerals to the impacts of a year of an individual’s life, and again finds them relatively low. All this, admittedly, makes one’s final, posthumous impacts look rather slight compared to the damage one might have caused over a whole lifetime. However, the cumulative effects of what we might call human ‘deathtimes’ are anything but trivial when it comes to the issue of burial space.

According to the Office of National Statistics, 529,655 deaths were recorded in England and Wales in 2015. While burial plots vary in size, a good average is 2.79m2 (1.98m x 0.91m with a 0.15m border on all sides). At that rate, burying just one year’s dead would consume approximately 1,476km2 – roughly 1% of the area of England and Wales. Of course, relatively few of the nation’s deceased are now buried: the Economist has put the cremation rate for the UK at around 75%. Assuming the remainder were buried, that still means an area more than three times the size of the city of Bristol given over to graves in 2015.

Of course, you can’t just go around burying people anywhere you like; only a relatively small amount of land is actually set aside for this purpose. Cemeteries have a spiritual and social function, and need to be accessible by communities, meaning that they must be located close to where people live. Extra capacity can’t simply be found by constructing new ones out of town. While the constraints are different, there’s an interesting parallel with landfills – which we were regularly told were rapidly running out of capacity before they ceased to be the final resting place for much of our waste.

City burial is especially unstainable, and a 2010 report from the University of York showed that eight London boroughs had already reached burial capacity, with another nine set to join them by 2020. This is why London has become the first city in England to embrace the reuse and sharing of graves, both practices made difficult by burial legislation. Since 2011, the City of London Cemetery has been opening up plots over 75 years old so that remains can either be excavated or, if the grave is deep enough, joined by a newly deceased. The cemetery sees this as the only solution which will allow it to maintain a respectful space while continuing to accept new residents into the future.

Going towards the light

Reusing grave plots may buy traditional cemeteries some time, but ultimately time is not on their side; it is time, after all, which will ultimately claim us all. It’s clear, though, that cemeteries serve an important function as a place of symbolic connection, offering a physical, tangible link between the departed and those left behind. For these reasons, some are embarking on new ways of thinking how funerary practices might better serve our changing needs.

Columbia University’s DeathLab is at the forefront of this work, bringing together a team of designers, engineers, architects and philosophers to offer reimagings of the infrastructure of death while honouring the need for public spaces of remembrance and reflection.

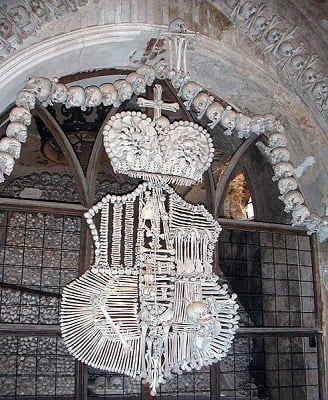

Coat-of-arm bones: a singular reuse of multiple human remains at the Sedlec Ossuary, Kutná Hora, Czech Republic. Photograph by Polyparadigm (CC-PD-Mark), via Wikimedia Commons

Recently, DeathLab won a competition run by Bath University’s Centre for Death and Society to design a future cemetery for installation in a corner of Bristol’s Arnos Vale Cemetery. The lab’s proposed ‘Sylvan Constellation’ is described as: “a network of memorial vessels which would transform biomass into an elegant and perpetually renewing constellation of light”. In the design, these vessels utilise microbial fuel cells to quicken the process of decomposition while converting the body’s bioenergy into electricity, which is then converted into illumination.

The vessels are either at path level or suspended overhead in the cemetery’s tree canopy, allowing visitors to stroll through a beautiful and otherworldly environment. DeathLab has calculated that the process of decomposition should take one year to complete, which would allow mourners time to work through the initial period of loss. Then the vessel would be ready for emptying, maintenance, and the interment of a new body. Such a solution, if it could be embraced socially, would both reduce the environmental impacts of funerals and solve the problem of burial space.

A hier-archy plane

Some might find it a desecration to think of human remains along the same lines as waste, but I think that a robust humanism can well accommodate the notion that we should conduct ourselves in death in the way that best preserves the corporeal realm for the living. This could involve the application of waste hierarchy type principles to the funerary process. For example, many – though nowhere near enough – people already register to donate their organs so that others may live if they should die; it’s hard to think of a more valuable form of reuse! Also, as we have seen, reusing burial vessels and spaces will be integral to ensuring the future of cemeteries, and new technologies may replace cremation and in doing so further reduce the environmental impacts of funerals.

There is a delicate and obscure line to be traced between our spiritual and environmental needs, but endeavours such as the Sylvan Constellation show that it’s possible to reimagine the funerary in a way that is both spiritually dignified and environmentally sustainable. Perhaps the most existential act in waste management is to begin to engage with how our own remains might be treated after we are gone.

Maybe we should Love Food, Hate Wakes?

I like the resomation (as there is some material recovery) and cryomation (not sure what happens to the shattered material). Personally – the shredder and compost heap at the bottom of the garden with someone turning the heap occasionally and hope the dog doesn’t view it as an alternative food source.