by Chris Cullen

7 minute read

Eunomia’s recently published 4th issue of its ‘Residual Waste Infrastructure Review’ continues to highlight the high (and growing) level of residual waste treatment capacity that is sitting with planning consent. If constructed, this will greatly exceed the amount of residual waste the UK produces and will hamper efforts to increase recycling and reuse.

The latest version of the review provided more information about a new and growing pressure on the volume of residual waste available for treatment in the UK – export under the guise of low grade Solid Recovered Fuel (SRF), i.e. Refuse Derived Fuel (RDF). In the report we took a reasonably cautious approach in estimating the amount of waste that will take this route, as we were anxious not to overplay this contentious issue. Our work now gives us a much better understanding of just how much residual waste we could actually send to Europe’s waste facilities, a topic that merits more in-depth discussion.

A forecast that changes the weather

The interesting thing about Eunomia’s forecasts of overcapacity is that they will ultimately (and hopefully) be a self-defeating prophecy. Indeed, the market is already waking up to the realities of potential future feedstock shortages and we’re regularly asked to carry out analysis projecting the availability of waste for investors or developers of specific planned facilities. Without confidence in long-term feedstock security, a given merchant plant is unlikely to receive any external finance that it requires. Competition for waste from European incinerators only exacerbates the uncertainty that is hampering projects looking to secure finance.

While there is good data on the current level of waste exports (from the Environment Agency and SEPA, DOENI, and the EPA), the growth rate used by Eunomia to forecast future waste exports was deliberately conservative. This is for a number of reasons:

- The limited track record of the relatively recent phenomenon of waste exports means there is a lot of uncertainty about how it will develop;

- A higher estimate of future waste exports would not have changed the overall message of the report; and

- We felt it was important not to distract from the central message that the UK is potentially heading for overcapacity.

The fact of the matter is that there is far more spare residual waste treatment capacity in Europe than we are predicting will be filled by waste from the UK. Many of our European neighbours invested heavily in waste treatment facilities years before the UK boom in energy from waste (EfW). Rapid increases in recycling have resulted in overcapacity, and a number of EfW facilities have already closed, most notably one of AVR’s incinerators in Rotterdam.

However, many facilities are integrated into the household and industrial infrastructure through the use of heat distribution networks. Closing them would not just be a problem for investors. Nor would it simply mean that a little more electricity would have to be generated by other means. Residents and industry risk being left in the cold. There is therefore an understandably strong motivation to secure feedstock.

European studies

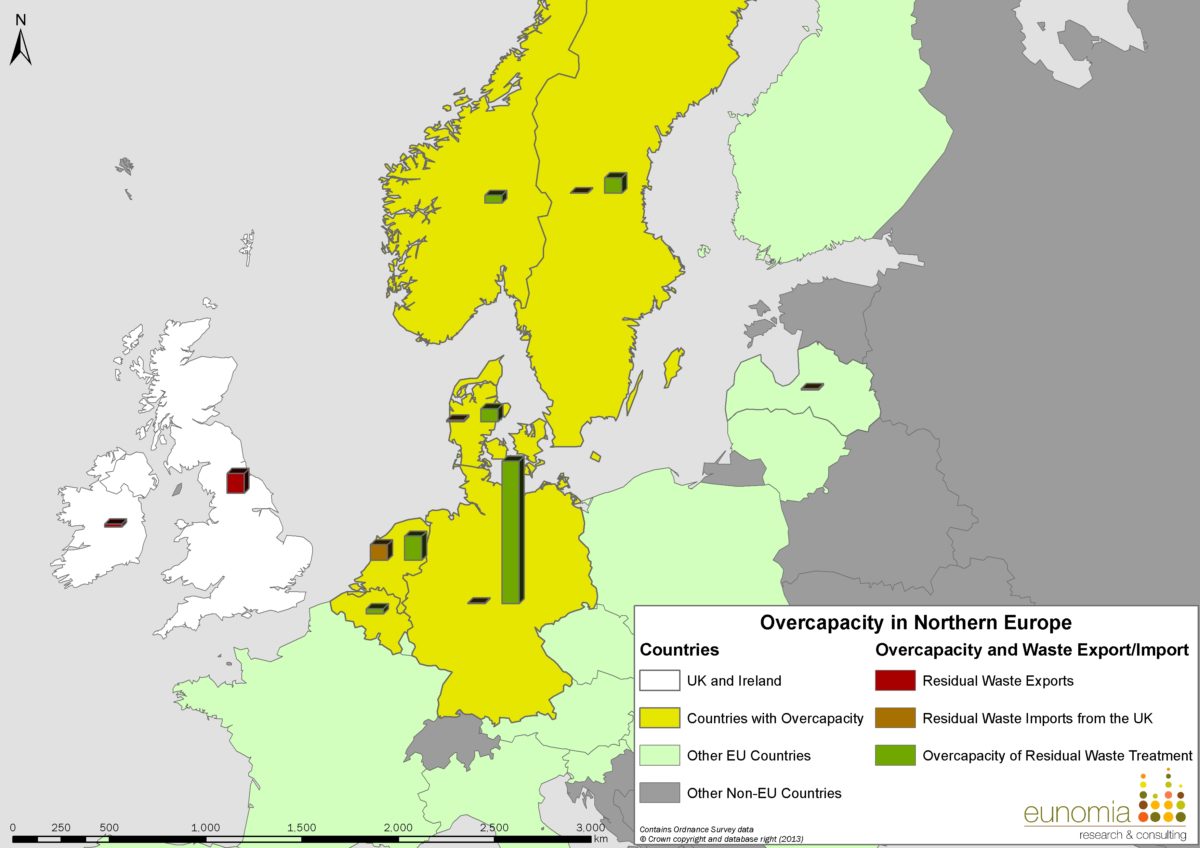

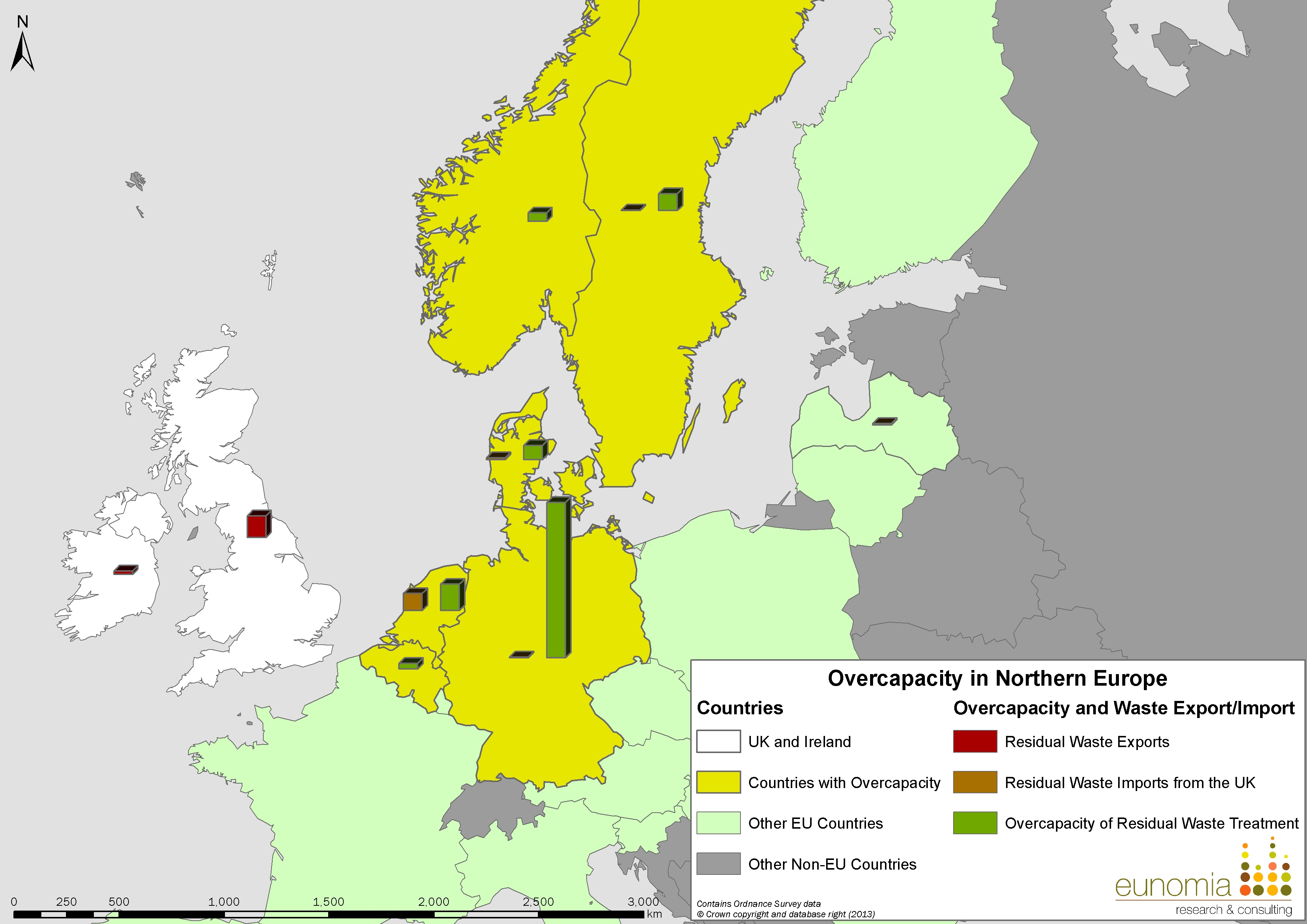

In preparing the 4th issue we reviewed several recent studies (including a detailed 2011 report by Tolvik Consulting and a number of more recent but somewhat more limited reports) that have examined residual waste treatment capacity in Europe. These reports detail the extent of the overcapacity that Europe is now suffering. Focusing on our closest neighbours in Northern Europe, there appears to be around 8 million tonnes per annum (tpa) more thermal treatment capacity than waste, spread across Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, Sweden, Norway, and Belgium, as shown in the map below, and detailed in the table.

| Export of RDF (2012) |

Estimated Overcapacity (tpa) |

Imported from the UK (tpa)[4] |

|

| UK[1] |

892,908[2] |

n/a |

n/a |

| Ireland |

86,911[3] |

n/a |

n/a |

| Belgium |

n/a |

200,000 |

n/a |

| Denmark |

n/a |

500,000 |

64,907 |

| Germany |

n/a |

5,550,000 |

29,341 |

| Latvia |

n/a |

n/a |

38,084 |

| Netherlands |

n/a |

925,000 |

596,595 |

| Norway |

n/a |

300,000 |

n/a |

| Sweden |

n/a |

600,000 |

15,928 |

| Total |

979,819 |

8,075,000 |

744,856 |

Germany has by far the most, a proportion of which can be attributed to RDF power plants and RDF co-incineration. If one looks further afield, as SITA has, at countries in central and Eastern Europe and includes facilities such as cement kilns, even more spare capacity can be factored in.

Some of the reports we’ve reviewed forecast a growth in overseas incineration capacity, as levels of recycling increase and the total quantity of waste decline, thus potentially driving increased demand for waste imports.

Capacity benefit?

The UK is well positioned and well motivated to fill the gap: we’re nearby, we still landfill waste and we have a high rate of landfill tax. So it shouldn’t be surprising that we’ve already begun to utilise some of the spare capacity, exporting around 900,000 tonnes of residual waste in 2012, up from around 300,000 tonnes in 2011, with only negligible amounts being exported in 2010 and before.

The rapidity of this growth is also partly driven by the determined and focused efforts being made by many European EfW facilities to secure short and medium-term merchant residual waste contracts. They are targeting the UK and Ireland, but their sights are also set on other EU countries that have more waste than treatment facilities. And of course, their gate fees are competitive on the UK market, even factoring in the cost of transport.

There’s also a fair argument that exporting waste is the green choice with many European facilities being more energy efficient than UK incinerators. Perhaps it is little wonder that even some UK local authorities – those not already committed to send their waste to a purpose built local facility – are actively examining the option of exporting their residual waste to Europe.

The trash ceiling

The European appetite for UK residual waste is growing, but two factors in particular limit how much UK residual waste might be exported. The first is the capacity of the overseas facilities: 8 million tonnes and rising. The second is our ability to fill that capacity. In 2012/13 the UK sent almost 19 million tonnes of residual waste to landfill (under the standard rate of tax), which is falling as we improve our recycling efforts and bring more new facilities on stream. The great majority of this would be suitable; but even a conservative estimate of 70% would put the amount potentially exportable at 13 million tonnes.

You don’t have to be a professor of calculus to spot that, if it wished, and if the capacity isn’t snapped-up by other countries with more waste than treatment, that the UK could supply all of the waste that European EfW facilities require tomorrow. Of course the pace of change is unlikely to be that quick, and not all of the waste is available or practical to export. Some is locked into contracts, and some is gathered at transfer stations in quantities too small to be attractive to overseas buyers who are looking for bulk.

Self-sufficiency in managing our waste is a goal that should not be lost sight of. However, rushing to build EfW facilities that have little prospect of securing feedstock to see them through their lifetime is not the way to do it. We can meet a good deal of our short term infrastructure needs through export. That will leave investment capital to be focused on developing the right kind of systems and infrastructure needed for a high-recycling future.

Over the next 10 years we should be focusing our resources on truly implementing the waste hierarchy, with residual waste treatment being the last option we contemplate. The heated debate over whether we should be developing much more incineration capacity needs to be placed in this context: the realistic aim of avoiding producing waste that it makes sense to burn will bring us the most benefit, both in terms of the economy and the environment.

[1] UK values are for England & Wales only. Scotland is exporting small but negligible quantities of RDF, as is Northern Ireland.

[2] Figure for England & Wales. Source: letsrecycle.com (2013) Sharp rise in RDF exports during 2012, 14 February 2013.

[3] 2011 figure. Source: EPA (2013) National Waste Report 2011, 2013.

[4] Values cover 16th October 2011 to 15th October 2012, and are for England & Wales only. Source: Data file received from the Environment Agency, 29th October 2012.

Chris

Since you wrote this I have seen articles suggesting that UK RDF waste could be out competed by waste from Eastern Europe which may be easier to bring in by rail. Have you considered this and does it affect the view you took here?

Hi Philip,

To date I’ve not come across anything of this nature, and our market intelligence suggests that this is not currently occuring. While waste may be transported easier, I’d be surprised if Eastern European countries could compete with the UK in terms of gate fees paid. However, in the long-term this is definitely something that that could happen, but in the short to medium-term I expect the demand for UK RDF and SRF from the Netherlands (and elsewhere) to remain quite high.

Chris