by Peter Jones

8 minute read

The number of fly-tipping incidents recorded by councils in England has gone up every year since 2012/13. In 2016/17, the total number of fly-tips exceeded a million for the first time since 2008/09. Around two-thirds of incidents are classed as involving household waste; the number of such cases has increased by around 41% since 2012/13 so it’s natural to ask what changes might underlie this dramatic rise.

As the numbers have gone up, the issue has regularly made headlines. The conclusion generally drawn by journalists is that an increase in fly-tips of household waste is probably something to do with councils offering less frequent residual waste collections. It seems obvious – faced with more waste than they can fit in the bin, people go off and dump the excess in an alley or lane. But does the data back this idea up?

Left in a hedge

In this article I focus on just two classes of fly-tip: “household black bag” and “other household”, as these are the ones likely to be affected by household waste collections. Before trying to draw any conclusions from the data, it’s worth noting that it comes thickly hedged with disclaimers from Defra. The department’s report on the latest stats notes a number of important limitations:

- The statistics generally relate only to fly-tips on public land, as these are the incidents that local authorities are responsible for clearing. Most fly-tips on private land go unreported.

- Some authorities make it easier to report fly-tips than others. Defra says that “several authorities reported that the increase in the number of incidents reported compared to previous years was a result of the introduction of new technologies; such as on-line reporting and electronic applications as well as increased training for staff and a more pro-active approach to removing fly-tipping.”

- The rules on what councils should count as a fly-tip are subject to interpretation: “there can be some differences in approach, where there is a level of discretion in using the guidance on reporting”.

So – it is possible that a change in the figures has nothing to do with any real change in fly-tipping. It’s also worth noting that, despite recent rises, the number of recorded incidents is still less than it was a decade ago, when weekly residual waste collections were more prevalent than they are now. But for the sake of argument, let’s take the stats at face value, and see what they tell us.

Region of doubt

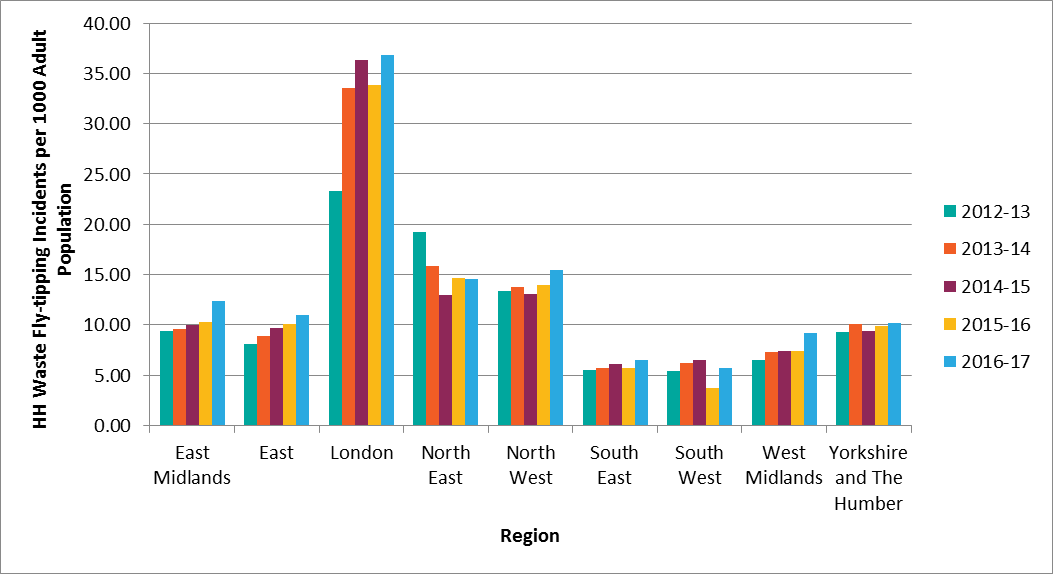

While most areas of England have seen an increase in incidents, not all have. The chart below shows incidents broken down by region. London reports the greatest number of incidents, and has seen the greatest increase since 2012/13, both in absolute terms (102,000 additional incidents) and in percentage terms (a 67% increase). The South West has seen only a 9.5% increase, while the North East has registered a 23% (9,500 incidents) decline. Where the North East was the region with the third highest number of incidents in 2012/13, it had the lowest number in 2016/17. So, what’s different about the North East?

Well, one third of the twelve local authorities in the area had retained weekly residual bin collections as at 1 April 2016/17, the second highest proportion of any region. But the greatest proportion of weekly bin collections councils is in London, where the biggest rise in incidents occurred. Of course, London can be seen as a special case – but in the South East, almost 33% of councils retained weekly bin collections, but the number of incidents rose by 22% (8,639). I’ve not been able to find any other policies or waste measures that explain why the North East should be performing better than the rest of the country.

Adults only

So far, we have been looking just at the absolute numbers, and ignoring the number of people in each area. To remove differences in population between regions and local authority areas, I have divided the number of incidents by the adult population (assuming that children don’t fly-tip) to allow comparisons to be made. The chart below shows the number of incidents each year per thousand adult population in each region.

This reveals a good deal of up and down variation each year, but shows the same overall pattern of increase from 2012/13 to 2016/17, with London showing the greatest increase and only the North East showing a decrease – although incidents per capita have risen there since a low point in 2014/15.

Is there evidence to support the idea that there’s a correlation between increased incidence of fly-tipping and reduced waste collection frequency? One place that one might look would be the few English local authorities that had moved to three weekly residual waste collections well before the end of 2016/17: Bury, Rochdale and Oldham.

Sure enough, the number of incidents per thousand adults has risen in each since they went three weekly. In the table below, the last year before the introduction of three weekly collections is shown in italics; the first full year of reporting under three weekly collections is shown in bold (Oldham switched during 2016/17, and so has not yet quite reported a full year).

| 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | |

| Bury | 10.2 | 9.7 | 15.3 | 20.1 | 14.4 |

| Oldham | 3.8 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 5.2 |

| Rochdale | 16.0 | 19.0 | 10.4 | 17.7 | 21.3 |

It would appear that both Bury and Rochdale have seen an increase in household waste fly-tips per 1,000 adults of more than 100%, while Oldham is well on the way to a similar increase. That said, Bury’s figure dropped a good deal in the second full year of reporting; and Rochdale’s 2014/15 figure seems to have been unusually low for the area, perhaps exaggerating the increase that followed the introduction of three weekly collections in 2015.

I haven’t been able to establish whether these authorities introduced new reporting policies at the same time as they changed their collection frequencies, or what the increase means. Some authorities class waste that householders leave next to their bin as a fly-tip; it’s plausible that, while three weekly collections are bedding in, such cases might increase temporarily. Or it may be that people were dumping excess waste in other locations – the figures just don’t tell us.

Frequent fly-ers?

It’s important also to set the figures for the three-weekly authorities in context. The chart below shows the change in fly-tips of household waste (over 5 years and comparing 2016/17 with 2015/16) split by the authority’s 2016/17 residual collection frequency. Surprisingly, the increase reported by the small number of three weekly authorities is little different from that found in the ~85 that collect weekly, while the 200+ fortnightly authorities have seen a much smaller increase.

The biggest change by far was seen in the 20 or so authorities that Eunomia’s records indicate operate a mixture of weekly and fortnightly collections for different property types. So, whatever we conclude about the impact of three weekly collections, it does not appear that collection frequency is the driver for an increase in reported fly-tips.

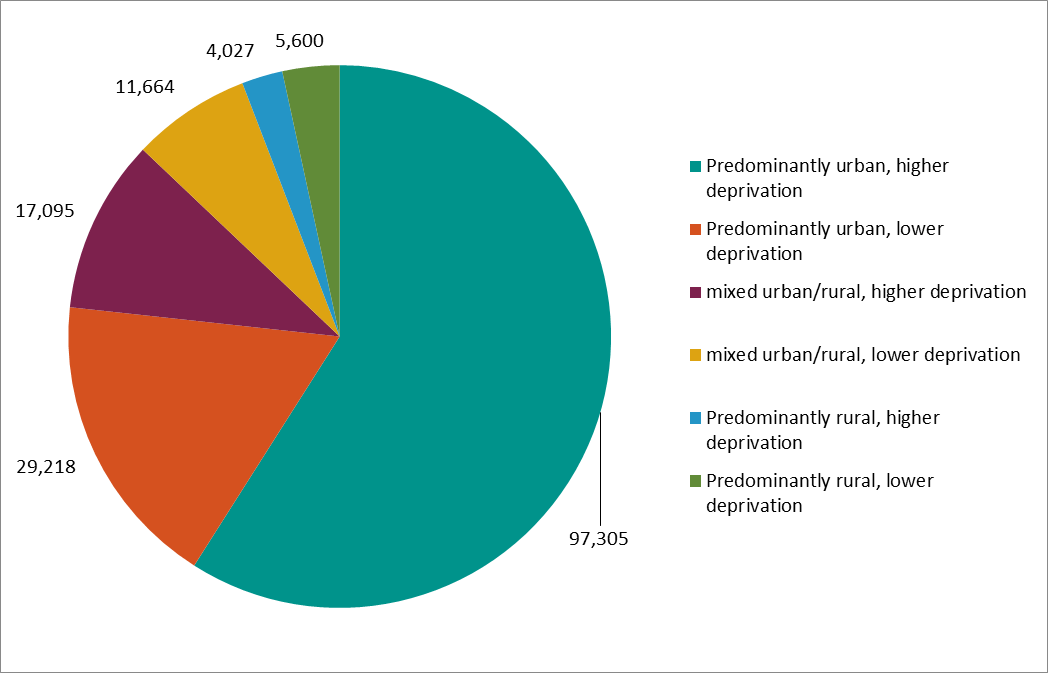

If collection frequency isn’t the reason, what other factors could be in play? The pie chart looks at the increase in the number of fly-tipping incidents over the last five years and divides it between local authorities classified by whether they are rural, urban or mixed; and whether they rank higher or lower in terms of deprivation. The results are striking: 59% of the increase has taken place in more deprived urban areas, and a further 18% in less deprived urban areas.

The cities were already where the greatest number of fly-tips were reported, but as the chart below shows, the gap has increased over the last five years. However, we cannot be sure whether this is because more fly-tips in rural and mixed areas are on private land and go unrecorded.

Leaving that to one side, if we disaggregate the issues of “deprivation” and “predominantly urban”, both are associated with a 35% increase in reported incidents over the last five years, although the number of fly-tips recorded per 1,000 adults is higher in urban areas than in higher deprivation areas.

London weighting

Most striking of all is that the figure for London authorities went up by far more than that for urban areas generally, and to a far higher absolute level. Perhaps that helps explain why it’s an issue that exercises the minds of national journalists! But even this intuitively appealing result masks a huge variation.

- Enfield Council, for example, reported 256 incidents per 1,000 adults in 2016/17 – a five year increase of over 270%;

- Wandsworth, by contrast, reported just 2.7 incidents per 1,000 adults, an increase of only 4%; and

- Barking and Dagenham, both urban and deprived, recorded just 4.8 incidents per 1,000 adults, a decrease of 65% over five years.

While this differential is extreme, throughout the data there are many examples of large, hard to explain differences from authority to authority and from year to year. In truth, the more closely I have looked at these figures, the more convinced I have become that anyone who claims to be able to use them to draw conclusions about what’s really going on simply hasn’t looked hard enough. That’s pretty unsatisfactory for a national data set, especially one that people have a real interest in understanding. But unless guidance is tightened to give greater assurance that councils use common definitions – or at least explain when an apparent change is due to a new local policy – that seems to be the most reasonable conclusion to draw.

I doubt there is a universal explanation for the variation in the reported changes – although data weaknesses probably apply in most cases. HWRC provision and policies is worth looking at. Restrictive policies on access to sites – the no van rule and the distance to alternative landfill or waste disposal facilities have an impact. Car availability will affect the willingness and ability of many households to transport excess waste to a proper facility and hiring a man with a van is no guarantee that waste will not be fly tipped especially if the van is expected to make a long journey to a commercial waste facility.

Frequency of collection of residual waste ( or more particularly the effective capacity offered for residual waste) probably has some impact but I too doubt it is a full explanantion.

Our local authority in North East Somerset have just introduced a now bin collection scheme. Each household has one bin for general rubbish which just about holds two black sacks, this is collected fortnightly in addition to weekly recycling collections. Sounds reasonable but… the lid must be fully closed & you cannot leave any other rubbish outside the bin, it will not be collected & you will be fined £60. I think there could be an increase in flytipping around the Somerset lanes very soon.

Hi Dave,

Thanks for your comment. I hope that this article helps explain why there is no evidence that a decrease in bin collection frequency is linked to an increase in fly-tipping in the lanes. Not sure if BaNES will count waste left next to the bin as a fly-tip. If they do, it would push up the figures.

But for many people there is lots more scope to recycle, saving your black bin space; and if you can drive your waste to a lane, can’t you just drive it to the HWRC at Bath, Keynsham or Midsomer Norton?