by Adam Baddeley and Peter Jones

6 minute read

Eunomia has been publicly warning for four years now that the UK’s “dash for trash” will leave us – like Sweden, the Netherlands and some of our other Northern European neighbours – with more residual waste infrastructure than we really need.

While it has been widely read, the message of our Residual Waste Infrastructure Review (RWIR) hasn’t been rapturously received, especially amongst those for whom the planning, construction and operation of incinerators and advanced thermal treatment is a major source of income. Indeed, it has spawned several imitations, perhaps intended to cast doubt on our conclusions and buoy up the market. However, we’ve found serious problems with the capacity reviews produced by Suez, CIWM and others, whilst so far as we are aware, no-one has taken issue with our methodology – except us, as we’ve refined it over time.

Circular argument

With Issue 8 of the RWIR currently approaching completion, it was somewhat gratifying to see the Local Government Association quoting November’s Issue 7 as a key source in its EU Circular Economy position paper last month. The position paper contains much that is laudable, including greater emphasis on producer responsibility, designing out waste, and stimulating the market for secondary materials. However, it warns the EU against a hike in recycling targets with the following argument:

“English local authorities have committed many hundreds of millions of pounds to underpin the delivery of waste treatment infrastructure to radically reduce landfill by 2020. This treatment capacity will process a volume of waste that will make meeting a suggested 70 per cent recycling target unachievable. Unless Member States’ committed investments are taken into account in target setting there is a risk that these expensive and long term facilities are made redundant leaving public authorities with large liabilities.”

Local government has been one of the key investors in residual waste treatment. The (now defunct) Landfill Allowance Trading Scheme (LATS) and Landfill Tax escalator provided the push, with Defra PFI credits providing the pull towards more predictably priced solutions for councils to tackle their expected tonnage of residual waste.

Diagnosis: burner

Of course, the LGA is right in its diagnosis. If the EU were to agree on a 70% recycling target for its Member States, for England to have any chance of achieving it local authorities would need to be in the vanguard. Yet if all of the facilities currently being constructed are completed, our numbers show that UK and local authority recycling will be limited to below this target level. If a higher recycling rate is demanded, it risks leaving some of England’s expensively obtained residual waste treatment capacity short of domestic feedstock.

Part of the aim of producing the RWIR was to alert investors in residual waste treatment to the growing likelihood that treatment capacity would exceed the supply of waste, as we have no wish to see facilities built only to be left idle – potentially at great cost to investors, whether public or private sector. However, little purpose would be served by simply telling local government “Well, we warned you”, and leaving them to pick up the tab.

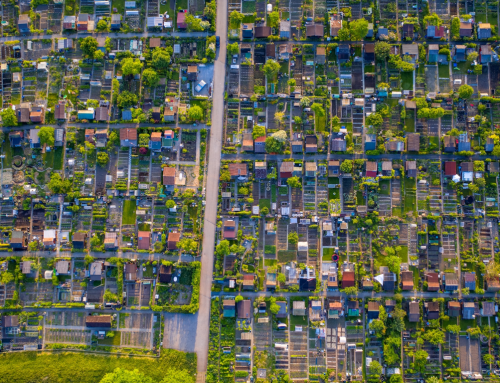

Under a cloud: excess incinerator capacity is set to be a problem for the UK. Photo by Marco Monetti (CC BY-ND 2.0) via Flickr.

Another motivation was to try to head off the all too foreseeable scenario in which recycling and incineration come into direct competition. Eunomia has warned that, as the role of landfill rapidly declines, recycling and incineration are – at the margin – competing for the same material. On both environmental and economic grounds, we would prefer to see resources devoted to increasing recycling rather than propping up incineration.

Change of prescription

In this context, the interesting issue is whether the LGA is right in its prescription – should the EU moderate its recycling ambitions to take account of “Member States’ committed investments”? Or are there alternatives that councils, which are already committed to significant pieces of infrastructure, should be exploring? Here are a few alternatives to what we would see as the councils’ representative body’s counsel of despair:

- Targets are typically set at member state level, and have much wider scope than just local authority collected waste. Instead of calling for less ambition on recycling, the LGA could ask government to support business to improve the recycling rate for other waste streams such as commercial, industrial, construction and demolition waste, to make up for the potential local authority shortfall.

- Equally, the LGA could reflect on the difficulties that councils are facing when it comes to increasing – or even maintaining – their recycling performance in the context of deep funding cuts and weak material markets. It could call on government and the GIB to support the much smaller investments needed to support the collection and reprocessing of recyclable material in the UK, making alternatives to incineration more attractive.

- The UK government has rightly been reticent about passing targets on directly to individual local authorities. Demographics have always played a role in recycling performance: numerous rural councils already achieve recycling rates in excess of 60%, while others (especially in inner cities) barely achieve half that. The fact that some councils have heavily constrained their recycling rate through a commitment to incineration is just one more factor to take into consideration. So, LGA could call on government to recognise these constraints when considering UK targets; and to support authorities that aren’t constrained by existing infrastructure to maximise their recycling, thereby taking the pressure off those that are.

- Eunomia’s capacity projections take account of treatment facilities that are at various stages of development. To ensure that England’s local authorities can play their full role in meeting a higher recycling target, the LGA could:

- Call on government to help some councils renegotiate their incinerator contracts to enable exit from any requirements that commit them to supplying a guaranteed minimum tonnage; and/or

- By supporting collaboration or trading between councils to allow waste to be matched with capacity.

- The waste a council sends to an incinerator does not have to come from households. The LGA could encourage councils to step up their commercial waste operations, or to actively encourage local commercial waste operators to supply waste to their incinerator to replace any shortfall in the council’s own material.

While it is encouraging to see the LGA at last taking note of the RWIR’s concerns, the lessons it draws from the study are certainly not those we would wish to encourage. Calling for less ambitious recycling targets may seem like the obvious solution, but many cheaper and more creative ways of dealing with the challenge of local authority incinerator overcapacity are available. We hope that the LGA and the councils they represent will be keen to explore them, preferably before the likelihood of a 65% or 70% recycling target becomes a reality.

An interesting debate and comments. I’ve always swayed towards the opinion that the overcapacity argument is something of a red herring. As was pointed out by Peter H the industry has had a pretty good time of it with PFI and 25 year ring-fenced tonnage deals with local authorities on MSW. That’s now gone and the economics barely stack up towards the overcapacity viewpoint in the medium term when you consider that the plants that are up and running and are competitive on gate fees (increasingly when factoring in landfill tax rises) on the European mainland are actively competing for UK waste -this surely has to continue to stifle UK waste infrastructure investment.

Unless English waste policy shifts markedly (and there is no evidence that it will) then I’m unclear where the levels of tonnage will be found in the future in a highly competitive, increasingly cross Sovereign border backdrop to warrant the type of investment that would get us towards over capacity -surely to look at the “financial picture in the round” involves this sort of wider perpective. The industry it seems is investing in RDF processing, bailing and shipping rather than “homegrown” energy recovery

Hi Bryn,

I’m not sure I share your optimism about the wisdom of investors or clients. Those 25 yr contracts are still very much with us, and facilities are still being built right now under those sorts of deals. In fact, the key issue that I think may explain our difference of view is the long lead-time for many EfW plants. We’re seeing projects under construction now, based on contracts that were let 5-10 years ago, based on plans made 5 years earlier. They may have seemed like the right plan back then, but a lot has changed in the meantime. The GIB has backed almost 2m tonnes of new EfW capacity in the last 2 years, throughout which period Eunomia’s Residual Waste Infrastructure Review has been warning of excess capacity.

The issue is – by the time overcapacity arrives, it will be too late to do anything about it (or at least, anything that isn’t terrifically costly). And if recycling targets go up, overcapacity will just get worse over time. The issue needs to recognised and acted upon before we create an even bigger problem for ourselves a couple of years down the line.

Mr Bryn Walters, We had not thought that this Isonomia article was still operational.

The opinion about the OVER-CAPACITY issue from OUTSIDE is that the Consulting Engineers and Advisors purposefully collude with the Client Base [the Waste Authorities, and Industry] to make the numbers high in order to validate the costs of proposed facilities and incidentally increase fees.

Take the example mentioned earlier where the advisors to a Corporation were cajoled by their advisors to place in their business case for the waste arisings that were initially over 800,000 tonnes per year – albeit a few years ago – and that after the enormity of interval between – this has now been reduced to 600,000 tonnes per year a figure which has been described as being “totally untenable for the City and area” but that for which the capital costs are still in excess of €590 Million with back fees to advisors (the Consulting Engineers and the likes) of well over €40 Million, and hyper-inflated land costs for the site quoted as being almost €60 Million. And this project is a Publicly-Finance one to a recently bailed out European Union country.

Such examples though are not rare at all.

A similar of not parallel programme – equally as recent – was a notorious project which became cancelled. This programme and project was to be arranged to deal with waste arisings of around the same number as the one above at up to 800,000 tonnes per year, but was cancelled after the Metropolitan City and the local people were dismayed that the outcome of pollution worries to the technology coupled with the extra-ordinary high costs which were recorded after tender at over USA $880 Million arose. Then as here the same issues arose about the “over-capacity” statements occurring. Thus despite cancelling the project – for which there was a fee of closure of $100 Million – an alternative option of making renewable fuels for transport from the same core base of up to 600,000 tonnes per annum of recovered waste, post recycling, at a capped figure of $190 Million is now likely to be accepted. This project we understand has been discussed at length within the Metropolitan Region as the generated revenue under offer has been quoted to give a revenue at sales of fuels alone at over $130 million per year and the initial gate fee for the recovered waste is offered to be Zero for the first 6 years and then a purchase cost at $50 per tonne thereafter with an indexed linking applied has made Metropolitan Region think more broadly about the issue. An important issue apparently was the very same as discussed in Isonomia and that as waste quantities start to fall over time they would not guarantee an floor quantity for the waste arisings and the Company has to take the risk – which it has stated it would.

In recent time within this country – including Northern Ireland – technical discussions with Waste Authorities from 2003 and onwards has shown an absolute reluctance to consider the issues in any way at variance to the standard metrics. At the various discussions that have taken place within this time frame the “Waste Industry” has been fixed upon looking at technology that is seemingly very expensive and based upon 20th Century technology of burning waste no matter what cost. So when we hear that when various companies were invited to be present at the various Waste Treatment Programme seminars arranged by the “Waste Industry” all they saw were the same Consultants and Advisors sitting around the Head Table – occasionally in different positions and roles – all espousing the same mantra it is hardly surprising that the Country is left in a time warp of “follow the leader” irrespective of the costs. So now when it comes to past these programmes and projects come up against the buffers of accountability. There is no such thing as accountability here since it seems apparently from the background in Isonomia inference has brought the position to light again.

Take a random example in waste to energy currently in discussion, a County Council area with a population of barely 600,000. It is alleged that they produce over 300,000 tonnes of residual waste post recycling! This is not credible at all, and we now know that the County Council and their advisors are fully aware of this. Another in a different county with a similar tonnage at 320,000 tonnes is alleged to be that arising from 580,000 residents: again this is just not credible. And when you see groups of these facilities arraigned around groups of cities (as in Yorkshire) the debate is really one which needs raking forward.

It is no doubt true that if too much energy from waste was built it could compete with recycling for tonnage, although that competition is influenced by contracts, by material values and energy incentives to name but a few factors.

The question being asked here is “what is too much?”, but the discussion will reach different conclusions dependent on whether we’re talking about “municipal waste” volumes, the total waste stream (including commercial), assumptions about future recycling targets, or any number of other influencing factors.

If we are looking at current capacity (built or being built), but projecting tonnes against 2030 targets, perhaps we should ensure that the nearly 5 million tonnes of municipal waste residual contracts that will come to their end in this period are added into the optioneering process.

Further it is true that the Eunomia capacity reports differ to the views of others, such as our report (SITA), the CIWM/AEA report and it would appear to me to also differ to the most recent report from the Green Investment bank. Why they differ is a complex array of data source, modelling boundaries, assumptions and perceptions that has been rehearsed a number of times.

What is important is that, in considering recycling targets, or perhaps ‘no waste targets’ (which include reuse and minimisation), we need to help politicians, of both domestic and international origin on what needs to be done, how to balance push and pull markets, to understand the costs of transition for both public and private sectors (that’s all sectors not just the waste sector) and then put in place the policy, market and (if necessary) incentive (push or pull) systems necessary to drive the change at the speed that all can accommodate.

As the LGA report rightly identifies this is a complex balancing act to make a transition from linear to circular and in my view is far more complex than the simple capacity discussion of energy from waste to recycling.

Hi Stuart,

Thanks for your comments. It’s certainly true that we need to help politicians understand the complex economics of waste and recycling – but are you not concerned that the rapid expansion of EfW risks making other, environmentally preferable options less viable?

I’m not sure it’s true that the different capacity reports are really so different as you suggest. Apart from the 15m extra tonnes of residual waste that the Sita Mind the Gap report had in its present day scenario compared with the RWIR, can you highlight any key differences in the assumptions of the reports that lead to the different conclusions? As far as I can see, on arisings, exports and many other key variables, the reports agree.

Hi Peter.

SUEZ is absolutely interested in providing the right treatment capacity ( wet residual, dry residual, recycling, remanufacture etc) at the right time. As a company investing in domestic infrastructure as well as SRF and RDF facilities and overseas placement, we have and continue to work hard to ensure that over the next 10, 20 and 30 years we provide the right facilities at the right locations. Our modelling on this issue has been ongoing for over 10 years and since the issue of the Mind the Gap report we have continued to update and refine our modelling and to act on its conclusions.

The original reply to your blog sought to bring one point to the fore, namely,’ contracts coming to an end in the next 15 years’ & its potential impact on the capacity debate but other factors such as financially fully depreciated facilities transferring ownership from private to public sector (as is the case in some PFI’s), new or revised targets, cultural change, new materials entering the waste stream and many other elements will impact on the technical and economic challenges/opportunities of providing affordable waste management solutions. Taking these factors together with numerous other assumptions is important and as your own updated report recognises the magnitude of some assumptions can be significant. For instance the assumptions you make on WID biomass conversion rates, rdf exports and waste growth etc will significantly influence the conclusions you have drawn.

My main point remains however, the task of delivering a transition to a more circular society is, as the LGA document identifies , complex. It requires a policy environment, market conditions and other factors to come together to deliver the affordable technical and cultural solutions required. Concentrating the debate around one single element of the LGA document does their work and the general debate a disservice. At SUEZ we focus on not only the capacity point but also on a multitude of other factors including , how to help linear industries affordably transform to more circular ones, to help waste producers avoid waste and to help public bodies achieve their goals in the most affordable way possible. These aspects deserve as much discussion as the residual waste capacity gap when considering the LGA document.

Hi Stuart,

While recognising that the transition to a circular economy requires action on many fronts, I think it is reasonable to point out that overinvestment in EfW could place an additional obstacle in the way of the transition that you and your colleagues at Suez clearly join us in supporting. The point of the article was to express concerns about Eunomia research being used by the LGA to call for less ambition in the EU’s circular economy package; and while we might both support other views expressed in their position paper, I hope we can agree that their position on recycling targets is not to be welcomed.

There are clearly complexities and uncertainties in the data, but the extent of 2030 overcapacity when set in the context of the possibility of a 70% recycling target looks sufficiently great that it would remain the prediction of any plausible set of assumptions. Colleagues have discussed elsewhere on Isonomia the issues they see with the other reports you cite, and I won’t rehearse those arguments here.

The 5m TPA of municipal residual waste treatment contracts you mention will, I hope, be less when they actually come to market due to increased recycling and waste prevention. Perhaps you would like to comment on how much of this waste already goes to treatment facilities, and what might be expected to happen to that capacity if the waste it currently treats goes elsewhere. So far, we have seen little evidence of facilities closing down, even when they reach the end of their operational lives: they are refurbished or replaced. So whilst these contracts present an opportunity to limit the extent of overcapacity, it is far from clear that they will be sufficient to avert it.

Gentlemen, your comments are very interesting and well presented.

Why not take away the subsidies altogether for these exceedingly expensive incineration (and by any other name gasification and other Att plants) and let them survive?

There can be no justification for local authorities paying to companies for waste to be treated when it does not exiat…this is a fundamental illegal tenet in waste treatment and something which the Public and Tax Payer is hardly being made aware of the implications. It cannot be right that a local authority can be forced to pay for the treatment of 400,000 tonnes of residual waste in a “named” area when it only has 150,000 tonnes. This is a preposterous situation and in terms of the failure would cost the Public and the Tax Payers over £80 Million a year for unecessary costs.

The proposal can be managed but why should the costs of treating the residual wastes be so high. There are companies that can make so much money fro the treatment of residual waste that they can now pay up to €uro 60-00 per tonne [UK Sterling £45-00] per tonne and still survive. The notion is very much being hailed within the other processes.

Thanks for your comments, Peter – I’m sure a process that could extract £45 of value from each tonne of residual waste would be widely welcomed.

Thanks for this good and interesting article. I’d take issue with one point though. If councils step up their commercial waste operations, there are cheaper places they can take the non-recyclable fraction of the new material they collect to avoid having to put it through an over-priced PFI incinerator. Landfill for example.

So if a council wishes to collect more commercial waste in order to be able to meet the ill-conceived GMT commitments it has made in the past, it will find – in many cases – that it’s commercial waste business is carrying disposal costs that make it uncompetitive.

Hi James,

Thanks for the comment – of course, a high disposal cost could make a local authority commercial waste business uncompetitive, but many councils compete in this sector on quality, not just price.

It’s important to look at the financial picture in the round. Expanding commercial waste collections might not be appropriate for all councils, but especially for those with “put or pay” contracts, filling the available capacity with income-generating commercial waste collections that simply cover their costs could provide scope to save money elsewhere – for example, through providing the headroom to allow new recycling services to be introduced.