by Phillip Ward

5 minute read

It will no doubt take Owen Paterson a few days to uncover all the issues Caroline Spelman left in his in-tray.

One which has dipped under the radar is the promised revised guidance on applying the waste hierarchy. Whilst it has been around for a long time, the hierarchy assumes greater significance now that the revised Waste Framework Directive gives its prioritisation of methods of waste treatment a statutory basis. Last year it was enshrined in England and Wales regulations that are now in force. Anyone creating or handling waste is already obliged to follow the hierarchy (Prevention, Preparing for Reuse, Recycling, Recovery or Disposal) and penalties can be imposed if they fail to do so. However, the guidance is a critical tool to enable the hierarchy to be applied in practice.

The hierarchy rightly admits of exceptions. It can be over-ridden where life cycle thinking shows that an alternative treatment produces a better environmental outcome. The existing guidance, for example, concludes on this basis that anaerobic digestion (AD) for food waste is preferable to composting and energy recovery is better than recycling for contaminated wood. The consultation which closed on 30th June is intended to refresh and extend the lifecycle evidence on which the guidance is based.

The burning issue

The challenge for Paterson will come when he tries to square the circle on energy from waste (EfW). Although there is no reason to think that the overall composition of municipal waste varies greatly at the regional level, local application of the hierarchy has so far led to quite different patterns in the handling of municipal waste.

Recycling rates vary by 10% points either side of 40%, but the use of EfW and landfill varies much more. Of course this is a moving picture. The transition from landfill is not complete nor is construction of EfW capacity. The low figures for EfW in the South West, for example, will change if the incinerators at Plymouth and St Dennis are built.

But there is another, more interesting reason why the figures differ. The current life cycle analysis-based guidance treats “black bag” refuse as a material in its own right and recognises a series of thermal treatment options as the preferred treatment method. But, of course black bag waste is not a single material. Resource Futures are the holders of comprehensive information about its composition and their study – published by Defra – shows that it is largely made up of regular recyclable materials and much of it is non-combustible.

Treating black bag waste as though it were a different material from recyclables allows local authorities to take sharply divergent approaches while still complying with the guidance. Some can focus on separating materials and maximising recycling; others can leave more material in black bags and incinerate it. If the new guidance continues with this broad brush approach to black bag waste then we can expect to see continuing divergence in waste treatments in different parts of the country, even though the hierarchy suggests that shouldn’t happen.

Of course, the guidance puts prevention of black bag waste ahead of thermal treatment. Compliance, you would think, must mean increasing efforts to separate recyclables out from the residual waste. But here the Government’s lack of ambition for England compared with the approaches of the devolved administrations in Scotland and Wales looks terribly depressing. It is difficult to see how an authority that achieved its recycling targets could be taken to task for failing to correctly apply the waste hierarchy – so low recycling targets may in themselves limit the extent to which the hierarchy can be enforced.

Contractual commitments

In the context of austerity, local authorities have to be acutely cost conscious, and will want to understand the cheapest way in which they can meet their obligations. Many might think that EfW would be hard to beat on price, but WRAP’s gate fees report shows that in fact it can be an expensive option – more so even than landfill in some cases. This should provide incentives to limit EfW to only what cannot be recycled, but in many cases local authorities that have commissioned incinerators are committed under a long-term contract to provide them with a certain volume of waste.

New Defra Secretary of State Owen Paterson. Picture by U.S. Department of State, via Wikimedia Commons

With recent falls in total waste arisings, which are now well below the predictions made when the investments were originally planned, meeting such a commitment could rapidly become more difficult, and deter the expansion of recycling. Planning constraints may block them from using out of area or non-local authority collected wastes instead. Authorities could face the dilemma of whether to apply the waste hierarchy or meet their contractual obligation to provide feedstock, which could amount to deciding whether it is cheaper to compensate their EfW contractor or to defend or pay any fines for failure to comply.

Meanwhile the EfW industry, buoyed by the increased support from the Renewable Obligations Certificate review, is expecting continued growth. They, and the local authorities that have signed up to long term contracts, will no doubt have contributed to the Defra review, to protect their position from any change in guidance.

We will see – and the guidance on the hierarchy will be a touchstone for where the Government is going on recycling and incineration in the future. Mr Paterson arrives in his new post with a reputation for disliking renewable energy subsidies and an antipathy towards wind farms. His views on waste may still be forming, and it will be interesting to see how he handles relations with the Lib Dem run departments of BIS and DECC on EfW once he finds out that incinerators divide opinions just as much as windmills.

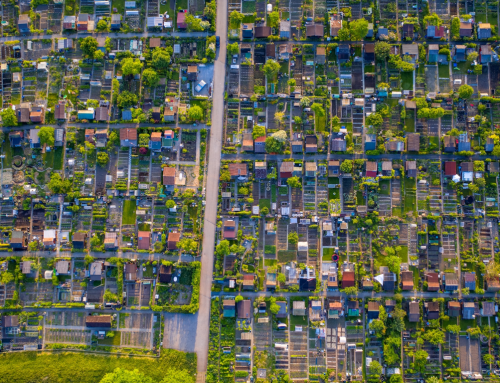

Featured image: Policy Exchange (CC-BY-2.0)

It is also alarming that the use of the Waste Hierarchy doctrine fixes in peoples minds that this is the only way.

The 4 Rs, Rethink, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle have different notions depending upon your background.

How about extending the area of Recycle to Reform? Reforming the chemistry or matrix of a commodity is equally as valid as a means of promoting recycling as it allows us to manipulate the ingredients so as to create alternative materials with a potentially better use and a longer life-style as well as being commercially better.

Here then is an example.After extracting the organic materials convert these to a Renewable Fuel or a Renewable Plastic. In the first we could say that the effect is a reduction in total use of fossil-driven fuels, in the second the plastics can be used as an alternative to the fossil-fuel choice. In both of these options the commercial optimum has to be considered, and in my view both are viable. As if not to be one that is the seller of the systems a renewable transport fuel made from the organic materials forming the core part of municipal solid waste is worth 4 times as much as making electricity from the same source of material. Manufacturing organic plastics is worth considerably more.

So let’s hear it again.

EfW divides opinion as much as politics!

Shortening contractual commitments is a good move to make sure the system is frequently optimized for recovery of materials and energy. 30 or 40 years without changes is too long!

It’s a difficult bind for local authorities. Investment in infrastructure has to be for the long term, but it is difficult to see many years ahead when the waste and resources market is changing so fast. The choices that some authorities made to invest in EfW incinerators looked like good financial sense when they were taken, but the increased value of materials and the growth in recycling has exceeded expectations, and authorities that guessed wrong may be stuck with infrastructure that no longer meets their needs.

Paterson’s appointment to Defra is an interesting one – I don’t get the impression that he has had a lot of reason to think about the waste sector in the past, and we may well see DCLG continue to make some of the running. There will be a fine balance to strike between piling costs on to authorities and undermining the hierarchy.

Do you suppose there is any scope for recognition of the value of investments already made in looking at how to apply the hierarchy – after all, money is another thing whose waste we should be looking to prevent!