by Dominic Hogg

5 minute read

It barely seems credible today to recall that in the late 1990s and early noughties there were people making policy – in what is now Defra, and the Environment Agency – who sincerely believed that it was incredibly challenging to meet a recycling target for household waste of 25%.

After one meeting of the Cabinet Office Strategy Unit reviewing a Waste Strategy that had been prepared in 2000, I remember a frustrating discussion in a pub with an official who asserted that ‘The most that can be recycled is 25%’. I asked what form of evidence I could produce to demonstrate that this was not the case. His reply was, ‘You couldn’t’.

Aspiration and inspiration

Much has changed since then. By the mid-noughties, recycling targets – routinely described as ‘very challenging’ at the time they were set – had been exceeded, and well before time. The 2007 Waste Strategy for England included more respectable targets, and ditched the 20 year forward projection of municipal waste growth at 3% per annum. The question became ‘is waste growing any more?’, and although we still lacked policy instruments to prevent waste, the programme on food waste developed by WRAP was capturing the imagination of environment departments across the world – even people to whom we had previously looked for inspiration. It wasn’t all world-beating stuff, but it was easy to see the early shoots from the seeds of genuine ambition.

At last, we were starting to develop a waste strategy that was not simply following a lead set in Brussels. The devolution of powers to Scotland and Wales has added a further dimension. Whose strategy would dare to go furthest and fastest? Whereas strategies have often been characterised by an absence of delivery mechanisms, Scotland and Wales are grabbing their new-found freedom to introduce these with both hands, and Northern Ireland may follow.

So where are we now? In England, there is a form of impasse at the level of Government, broken only by the annual landfill tax escalator, whose last scheduled increase will come next April. Undoubtedly the tax exerts an influence, but beyond this the impetus for change appears weak. Although the waste framework directive required the waste hierarchy to be implemented, our approach appears to have been designed to generate a low-key hiss rather than a bang.

A nudge is enough?

The Coalition’s policy of using voluntary agreements and responsibility deals to engender change was neutered by the tactical blunder of announcing, at the same time, their disinclination towards new regulation and policy. Voluntary agreements that lack any threat of alternative policy have one hand tied behind their back.

Defra has been working on its waste prevention programme, a new requirement of the Waste Framework Directive. There are some hopes that this will include some innovative measures, but powerful new policy instruments might be too much to expect.

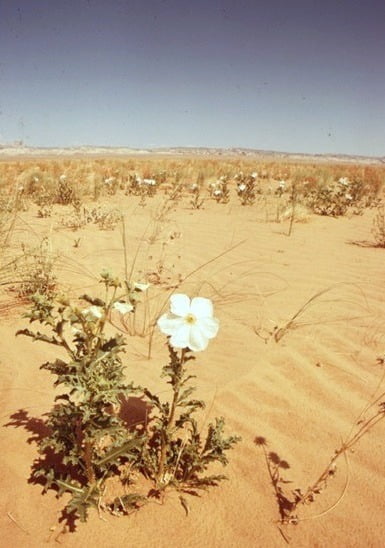

England needs to show a little blooming ambition on waste. Photo by Boyd Norton (NARA), via Wikimedia Commons

The Coalition’s record in respect of waste is poor. The preference for “nudges” over tried and tested levers resembles an attempt to develop a functional square wheel in place of a perfectly functional round one. The periodic, clumsy announcements from Mr Pickles in DCLG would be a major embarrassment in other policy fields. While seeking to oversee severe cuts in public expenditure, he has:

- Removed the power of local authorities to introduce pay as you throw schemes, which would encourage waste prevention and cut costs;

- Spent £250m trying, with very limited success, to encourage local authorities to re-introduce weekly refuse collections; and

- Most recently, spoken out against councils charging to meet the costs of garden waste collections.

Despite the cuts being demanded in local government spending, Mr Pickles keeps asking local authorities to spend more money on waste services and pay scant regard to the waste hierarchy. A clear indication of the Coalition’s lack of interest in waste and resource matters, and its fairly abject policy record in this area, is the fact that he has not been rebuked.

Efficiency deficiency

Nevertheless, like a rose blooming in a wasteland, interest in resource efficiency still thrives among industry and delivery bodies, nurtured by lateral roots reaching into Scotland and Wales. However, the policy discourse remains somewhat poorly developed. Exhortations to ban specific materials from landfill seem to overlook the real practical problems this presents for all but a few materials. The rather obvious point that ‘not landfilling’ may not mean ‘lots more recycling’ is a penny that stubbornly refuses to drop. It is no coincidence that countries with landfill bans also tend to have excess treatment capacity, now being offered to UK takers at extremely competitive rates.

None of the above is intended to deny the rising significance of materials value, which is influencing debates around the quality of collections and of sorting operations. One interesting effect of the spending squeeze on local government has been the quest for more financial ‘resource efficiency’. As materials increase in value, so the prevention of waste, its management as a material resource, and the quest to keep a lid on spending, have become ever more closely aligned. At a time of austerity, a greater appreciation of this alignment would have been welcome.

Policy documents around ‘energy from waste’ remain somewhat confused about its proper role, and whilst Defra’s ‘Guide to the Debate’ shows a better appreciation of the relevant issues surrounding incineration than in the past, National Policy Statements on Energy and Renewables are sufficiently woolly to be pulled over the eyes of planning inspectors.

There is a golden opportunity for further progress to be made around waste in the UK. Many of the fundamentals are in place, but the apparent resolve on the part of the Coalition in England to introduce no new polices of any import is disappointing. There are a diminishing number of pieces that still need to be put in place in the waste jigsaw, but for the time being the Coalition has put them out of reach.

A version of this article also appears in the June 2013 edition of the ENDS Report.

The 25% target was originally set in 1990 to be met by 2000. (Actually the original target was 50% by that date “This Common Inheritance White Paper” but that had to be redefined in the face of protest to 50% of recyclable waste – then thought to be half of the total). The difference in Waste Strategy 2000 was that some drivers of change were introduced – LATS – escalating Landfill Tax and WRAP as a mechanism to identify and reduce market barriers.

What we now understand is that there is relatively little in the waste stream which is technologically not recyclable and application of the waste hierarchy should lead to very high reuse/recycling rates. The barriers are now largely logistical (often confused with economic) and behavioural. A 70% recycling rate requires 90% of the population to consistently recycle 80% of their “waste”. To get to that level in my view we need recycling to be the default option wherever people are – at home, at work, at leisure, travelling. We need connected up thinking on this – but we are getting laudable individual initiatives that lack consistency of approach and messaging and little consistent incentivisation as government constantly tries to find ways of avoiding the logic of EU Directives and the waste hierarchy in the interest of cutting red tape.

Dominic,

I certainly agree that our efforts seem to have stalled.

I believe that there needs to be an open and lively debate between industry/local authority, policy makers, regulators and investors on how to generate momentum.

Strong and clear regulation has been proven to provide a strong foundation for innovation and investment. I believe there is an opportunity to do this with the focus firmly on the Waste Hierarchy.