by Hattie Parke

7 minute read

For anyone attempting to keep abreast of waste issues, it can seem like it’s impossible to escape calls for banning certain materials – or all materials – from landfill. As someone with both a professional and personal interest in food waste, it’s a recurring theme I’ve become acutely aware of because it’s so prevalent in that part of the waste world.

Targeted bans seem to hold a special attraction for those working with specific materials –you can see that an organics processor will have an interest in ensuring food that they could be using as feedstock doesn’t go to landfill. Calls for landfill bans are increasingly being presented in the context of the circular economy, valuing resources, and, in the case of food waste, ensuring that scandalous quantities of food surplus and waste are put to good use. However, advocates of bans seem not to have properly thought through what the ultimate fate of these diverted materials would be.

Merely diverting it from landfill seems likely to result in material simply falling through (into?) another hole in the policy landscape. If we’re to ensure that resources aren’t wasted, we must ensure that the policy changes we call for are likely to bring about the effects we want to achieve. A landfill ban, even if it can be enforced, ensures only that the banned waste doesn’t go to landfill, and says nothing about where it goes instead. In short, unless the only objective is ‘not to landfill’, then we must stop talking about landfill bans.

Out of the ban and into the fire

The argument seems to be that banning a specific material from landfill will lead to it being recycled instead. But it’s rather baffling to hear this put forward from people in the waste industry who might be expected to have a clearer view of the reality of the situation.

Put simply, banning food waste from landfill will not ensure that it is collected separately, and managed in the most resource efficient way, when much of the unrecycled food waste no longer goes to landfill anyway. In England, in 2014/15, 6.4 million tonnes of residual waste collected by local authorities ended up in landfill. Rather more, 7.8 million tonnes, was sent to incineration with energy recovery. Meanwhile 5.5m tonnes of residual waste treatment capacity – not all of it destined for use by local authorities – is at financial close or under construction, and therefore, quite likely to come on stream within the next three years.

In this context, what actual effect would any landfill ban have? First, consider all those local authorities already sending all their residual waste to EfW incineration facilities; a landfill ban would clearly have no impact on them. How about those not currently sending residual waste to residual treatment facilities? Well, the figures suggest that many will soon be doing so, and so the number making significant use of landfill by the time any ban proposal made its way through parliament would be likely to be very small. Any remainder could potentially satisfy a ban not by recycling more, but by exporting residual waste for treatment on the continent.

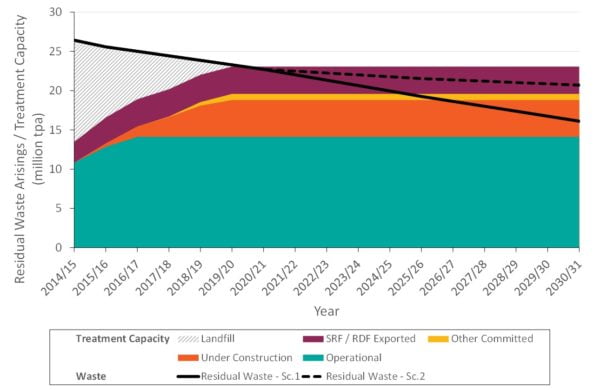

This trend towards incineration is reflected in the treatment of commercial waste, too. Indeed, Eunomia’s latest analysis of residual waste infrastructure shows that by 2020/21 there will be sufficient residual treatment capacity to treat all residual waste (both household and commercial) in the UK.

We’ve nearly had our fill: demand for landfill is rapidly being squeezed out. Source: Eunomia Research & Consulting

A previous Isonomia article explained that EfW is a far from ideal treatment option for food waste, but it is already the end destination for a good deal of this material contained in residual waste, and all the indications are that the amount will increase in the next few years. A landfill ban seems unlikely to change this picture.

Burying our heads in the ground

Why then all the talk about landfill bans? I believe it largely comes down to three factors: what landfill represents, the difficulty of presenting a more complex, realistic picture of the waste landscape to the general public, and a misunderstanding of the position in respect of key issues, such as climate change.

After several decades of environmentalists ramming home an anti-landfill message, ‘landfill’ has become a byword for wasted resources and environmental harm. European institutions have also tended to assess country performance in terms of ‘how little waste is landfilled’. If you want to reach as wide an audience as possible, it helps to simplify your argument and use terms that people understand. Therefore, those wanting to make the point that food is being wasted talk about food going to landfill – despite this rapidly becoming a confusing anachronism.

Hoisting the banner

A recent article in the Independent is a case in point of an oversimplified message trading on ingrained aversion to landfill. It asserts that: “Pressure is mounting on the UK Government to introduce legislation to ban supermarkets from sending unsold food to landfill.” The article goes on to refer to the recent law passed in France requiring supermarkets to establish agreements with charities for the redistribution of surplus food.

A landfill ban and a law to promote redistribution of food are two very different policy instruments, and would have very different outcomes. A landfill ban wouldn’t necessarily change anything regarding the redistribution of surplus food; equally, many supermarkets already landfill very little food waste, so efforts to increase the amount they redistribute might have very little impact on the quantity landfilled.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, therefore, whilst the article irrelevantly describes the damage to the environment from food waste ending up in landfills, there is no mention of the resources wasted or the environmental consequences of such wasted production – even though one benefit of a food waste redistribution policy would be to reduce the generation of food waste.

These policy outcomes are also differ enormously in their climate change impacts. All too often, though, the reporting of greenhouse gases coming from ‘waste’ also shows an undue emphasis on landfill emissions. A recent Eunomia report shows how this tends to distort how we address climate change emissions from waste, and to entrench the view that we just need to ‘not landfill’.

Holes barred: talk of landfill bans should fall on deaf ears. Photo: Roger & Renate Rössing, Deutsche Fotothek (CC BY-SA 3.0 DE), via Wikimedia Commons.

While it’s good that people are concerned with the negative impacts of waste, policy makers need to shift their sights to higher levels in the hierarchy. Simply ensuring that waste is not landfilled – the only thing a landfill ban does – is not good enough. Those promoting better resource management need to update their messages, and their policies, accordingly. Bans can simply lead to a switch from residual waste disposal to residual waste treatment, with potentially limited environmental gains.

Ban quit

What are those calling for landfill bans trying to achieve? Ultimately, it shouldn’t be about keeping residual waste out of the ground, but the preservation and more efficient use of resources. We already have the waste hierarchy as a guide to how to go about this, and an antagonistic infatuation with its lowest tier is not the best way to aim for its top. In order to do that, we need policies which actually target the higher tiers.

There are a few different options here, but in principle the policies need to encourage their best use within a circular economy. In the case of food waste this means redistribution to people where possible, followed by feeding food waste to animals, and finally, treatment of separately collected food waste via anaerobic digestion. There really should be little need for food waste to end up anywhere else.

Focussing on landfill represents a singular lack of ambition; we need to start aiming higher – so let’s please stop talking about landfill bans.

This article is missing the point as does all regions that strictly talk about landfill bans in its strictest sense. Yes I agree that banning material from landfills will drive waste to the next disposal option which often a worst scenario being incineration. What needs to be done is a simple change in terminology and policy. Instead of a landfill ban they need to be disposal bans which include all facilities that are created with the intention of waste disposal such as; landfills, incinerators, waste transfer stations and dirty MRF now termed mixed waste facilities… or any other facility created with the intent to dispose of waste and not re-use or recycle it. (note, this would include anaerobic digesters that accept organic material micmxed with other non organic materials.)

I don’t think landfill bans are our main concern!

I think EfW with a long(ish) term need for residual waste are the bigger risk. Especially when so few are truly efficient in the generation of heat and power! In effect any incinerator that does not meet the R1 standard is a disposal operation, regardless of if it produces electricity or not! It would therefore; be deemed to be no different from landfill (which can also generate electricity) in the eyes of the waste hierarchy.

An incineration tax for non R1 EfW would seem reasonable., as it would help to divert waste further up the hierarchy and crest scope for investment.

Harriet makes a robust case. Sadly we often choose sub-optimal policy options in the UK because the direct option – in this case forcing local authorities and businesses to have separate food waste collections seems too authoritarian (for lack of a better word). Telling what they can’t do with a particular waste stream somehow seems more attractive to politicians and when the bottom end of the waste hierarchy was landfill a ban may have seemed the way to go. But for the reasons Harriet sets out it is a busted flush so a more direct approach makes much more sense. My main concern is to see a politician in England show any sign of grasping the issue in any way at all

With devolved administrations proving much less reticent about direct interventions, perhaps good evidence from Scotland and Wales will prove persuasive, even in England. I hope the waste sector will throw its weight behind efforts in that direction, rather than backing anachronistic calls for landfill bans.