by Ad Lansink

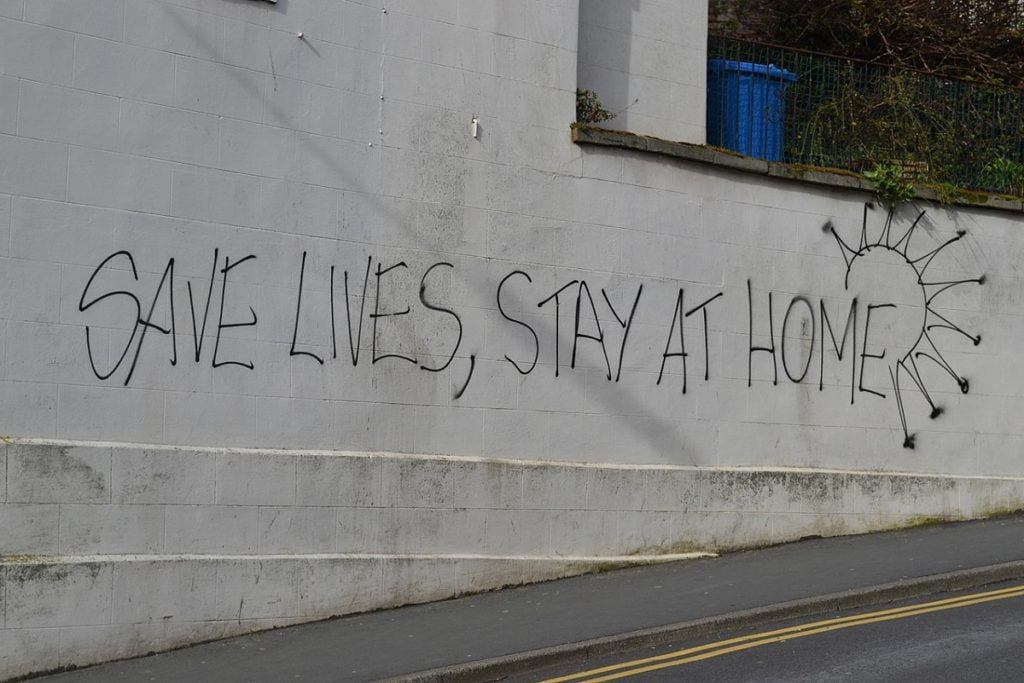

7 minute readThe COVID-19 pandemic has exposed new risks in our interconnected, global economy. The spread of SARS-CoV-2 has been greatly accelerated by high speed global travel, and resource pressures – notably, the challenge of securing personal protective equipment – are laying bare the fragility of our globalised, just-in-time supply networks. Moreover, as stated in a guest article by leading experts, recently published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES):

“Recent pandemics are a direct consequence of human activity, particularly our global financial and economic systems that prize economic growth at any cost.”

On the one hand, in 2020 and probably beyond, health and well-being will take precedence over prosperity and employment. On the other, for the time being, attention is also deflected from climate change, which is parked as an issue of secondary importance at a time when a more immediate problem must be faced. In some countries, including the Netherlands, climate measures have been partly postponed, and differences have emerged over the European Green Deal – although the EU appears to be moving ahead. A proper, long-term response to the crisis should ensure that we do not carry on creating environmental conditions that increase the probability of future crises. It also gives us a chance to learn about how we respond to large-scale international crises.

Cares of the world

The COVID-19 outbreak is a profound wake-up call, the lockdown an unmistakable signal that the global economy must change course. Rich countries, in recent decades, have put too much emphasis on economic growth, in a market that is too free. Countless product lifecycles, from design and production through to use and disposal, take place over large, international value chains, aided by complex logistics processes, both physical and digital. Security of supply seemed to be guaranteed by trade treaties, with global interdependence making geopolitical concerns appear superfluous. For companies, stockpiling seemed to be an unaffordable inefficiency, as did ensuring they had sufficient financial buffers in place. The pandemic, however, revealed the dangers of modern supply chain management.

Contrary to globalisation, responses to COVID-19 are controlled along national lines. In crises, everyone retreats into their own domain, behind their own borders – which may offer only false security. The differences between continents, and especially between countries, in how the pandemic has played out can only partly be explained by social and cultural patterns. We have seen a range of responses, from quick and decisive measures in Taiwan and South Korea, to more faltering steps in the Netherlands and UK.

Ask the experts

Where lockdowns have been implemented, the turnaround we see after four to six weeks is due to three essential factors: the action of the authorities, the dedicated and resilient service of key workers (health care, fire brigade, police, public transport, food chain, waste management) and, almost everywhere, an exemplary acceptance by the public of measures that might previously have been considered intolerable. Whether the high level of social unity will remain is hard to predict, but the resilience of society in the current time of need offers hope for the future, when climate policy once again receives the attention it deserves.

In the meantime, we live with a puzzling paradox: keeping physical distance while reducing or bridging mental distance. Although most have, metaphorically, come together in national efforts, there have been dissenters who disregard the advice of government and experts, either calling for a complete lockdown or return to business as usual. Often, these are the same people who oppose the necessary action on climate change.

The fact that these things have not happened is attributable to the trust political leaders have placed in the epidemiological experts in the fight against the corona virus. Such trust in scientific experts should, and must, carry through to policy on climate change and, by connection, the transition to a circular economy. When the end of the corona crisis approaches, government and society must bring the same perseverance to bear on ensuring a consistent long-term policy on energy and raw materials. Here too, it is heeding signals from science and following expert guidance gives us the best chance of success.

Pillars of society

The future is uncertain. Some trend watchers expect society to return to the old pattern of the linear economy, whether nations are driven by autocratic regimes or democratic governments, and whether following liberal or non-liberal ideologies regarding growth of production and consumption. A mature society, however, will benefit more from a selective, manageable and socially sustainable circular economy; social circularity, on a regional, national or international scale, depending on circumstances. The strengths of modern globalisation must be harnessed when working on an international scale, in terms of the sharing of norms and values, of knowledge and insights.

Following victory over COVID-19, an all-embracing policy approach to creating a socially sustainable circular economy would be based on the following pillars:

- A strong role for government, which can keep a grip on production and consumption by means of various management instruments, including taxes, but without lapsing into a planned economy.

- Internationally regulated market forces, such as the system of European directives, which are tested and amended by the European Parliament.

- Social and economic strengthening of developing countries through knowledge transfer and fair payment for the raw materials they produce.

- Sensible consideration of national, international and global ambitions, taking account of social and cultural perspectives in addition to economic and financial aspects.

- Connecting climate policy to the transition to a circular economy, with an emphasis on resource hierarchy, and assessing criteria of time, place and function in relation to the value chain.

- Changing commodity and waste policy using Industry 4.0 tools, such as new logistics management, global networking and blockchain technology.

- Ensuring strong public support, similar to that seen in tackling the corona crisis, through optimal information, communication and use of digital channels.

Fiscal fitness

Transnational cooperation is in any case necessary, even where the jurisdiction over measures and instruments lies with national authorities. The European directives provide good examples of supranational legislation, enacted through cooperation of this kind. When the free movement of people and goods is the starting point, supranational coordination, and even harmonisation, of financial policy instruments is of great importance.

In the fiscal domain of climate policy and circular economy, the following policy pillars apply:

- A partial shift from taxation on labour to taxation on products, while maintaining the principle of solidarity and carrying capacity in income taxation.

- Value added taxes, distinguishing between (higher) VAT on products and (lower) VAT on maintenance services.

- Appropriation levies, where all or part of the revenue is used to co-finance projects in the same domain, for example: CO2 tax revenue spent on sustainable energy projects.

- Corporate income tax, with the possibility of differentiation according to criteria linked to the objectives of climate policy and circularity.

Acts of solidarity

The COVID-19 pandemic is going to leave traces, especially in the public domain. The slider on the line between market and government is set to move towards more control and regulation. Hopefully, society will extend today’s solidarity into even greater sharing, involvement and solidarity tomorrow.

It is premature to use today’s harsh reality as basis for predicting a drastic change in economic system. Europe is not served by a modern form of planned economy, nor by the other extreme of complete economic libertarianism, in which there is room only for the strongest enterprises and institutions. What is required, however, at global, European and national levels, are political institutions that provide a framework for a new socio-economic order.

Politicians and policymakers need to take the lessons from the response to the current corona crisis as they formulate and implement the policies needed to address climate change. They will need to take account of social and cultural perspectives, as well as economic and financial ones, with the aim of achieving the same sense of solidarity we have seen in the corona crisis response in our global efforts to halt climate change and the environmental destruction – thereby also making future pandemics less likely.

Featured image: Zakhx150m (CC BY-SA 4.0), via Wikimedia Commons

Leave A Comment