Earlier this month, Glasgow declared its ambition to be the first Circular City in Scotland.

It joins an ever-increasing list of cities worldwide, though chiefly in Europe and China, which are adopting circular economy agendas and strategies as a route to resource efficiency. As an alternative to the traditional ‘take-make-dispose’ process of production and consumption, the circular economy is centered on designing out waste through improved materials, products and systems, as well as business models.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation suggests that local policy makers and planners play a key role in embedding circular economy principles across urban policies and functions. That applies to decisions about:

- what is built – the circular economy needs suitable infrastructure to support it;

- how it is designed – buildings, too, can be designed with resource efficiency in mind; and

- how it is built – there are more and less resource-efficient building practices.

But how does this ambition get turned into action? Why is there skepticism about the circular economy in the construction sector? What challenges and opportunities should we be aware of? Research I conducted this summer sheds some light on the answers.

Capital planning

My investigation spanned nearly all of the 33 local planning authorities in London. They’re encouraged to respond to the London Waste and Recycling Board’s (LWARB) 2015 Circular Economy Route Map, and must follow the London Plan when making decisions about spatial development. The new Plan, released in 2017 and currently in draft form, contains a whole section on circular economy policies. It is a key moment, therefore, to consider what the circular economy means for local planning in the city and how ready they are to act upon it.

In recent years, councils have had to grapple with a squeeze on public finances alongside new statutory requirements and an increase in planning applications. Local responsibility has been heightened without a concomitant shift in resources. Numerous planners I spoke to highlighted how reductions in officer numbers, time and capacity make it difficult to hold meetings and gather evidence – without which, it’s harder for planning teams to learn about how to implement new ideas and agendas.

A more circular economy can bring significant cost savings and wider benefits, yet within the confines of austerity, local planning authority decision-making is risk-averse, time-pressured and often involves path dependency; the continued use of a product or practice based on historical use or previous commitments rather than creating an entirely new path.

Respondents pointed out that, faced with trade-offs and pressures, novel circular economy thinking rarely features in planners’ considerations. Those pressures are significant: a number of London boroughs have seen their housing targets double or triple. Ultimately, as one planner explained, the circular economy gets sidelined by the bigger strategic political priorities.

Broad spectrum

A second complicating factor is the varied level of awareness and understanding amongst planners regarding a) what circular economy means, and b) how it applies to the built environment. I encountered the full spectrum, from substantial knowledge to a complete lack of awareness.

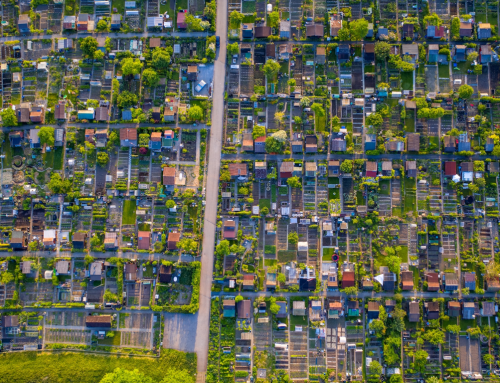

London shows it’s time for local authorities to build the circular economy into the planning system. Photo: David Holt (CC BY 2.0), via Flickr.

Some were unsure how the circular economy applied to planning, whilst others saw synergies between sustainability and place-making. This is important because planners play a key role in translating higher level circular economy policies into local, measurable and enforceable targets.

In the absence of more widespread expertise, the expectations placed on planners risk outstripping their ability to incorporate new thinking. There’s a real need for training and skill sharing to support them in developing the know-how to make informed decisions about how to ensure reasonable circular economy features are included in projects.

Proactive planning

Despite these challenges, planning authorities do possess tools and levers to instigate, or at least facilitate, change. In London for instance, the Mayor’s draft London Plan makes reference to a circular economy across multiple areas of activity, including Good Growth, Design and Sustainable Infrastructure.

Notably, Policy SI7 introduces a ‘Circular Economy Statement’ which all referable planning applications will have to submit. It covers how resource efficiency will be achieved both in the construction process and in the design, use and end-of-life of buildings. Whilst guidance is yet to be released, London’s policies appear set to encourage more widespread action on material re-use, resource efficiency and the application of circular economy design principles.

Construction round-up: applying the circular economy to construction. Source: Building Revolutions (2016) David Cheshire, RIBA Publishing.

Individual borough plans have to comply with the London Plan, with the result that the circular economy will have to be considered at a local planning level. Moreover, the practice of local plan making offers prospects to align land use and building design with circular economy principles such as adaptability and design for disassembly.

While the London Plan remains in draft, some projects are already adopting its principles. In west London, for example, the masterplan for the Old Oak and Park Royal regeneration project draws upon a circular economy approach in relation to the site’s design and construction. Eunomia has worked with the developers to help them design in the necessary space and facilities to allow for resource efficient waste management for commercial and domestic premises within the development.

A key to success is introducing circular economy development dialogue at an early stage. Planning Performance Agreements (PPAs) and pre-application discussions, for example, offer crucial opportunities for local planning authorities to play a proactive role in designing the circular economy into the built environment.

This is important because PPAs are increasingly popular components of planning practice, in part due to their utility in development value capture. Ultimately, planning can play a role in establishing rules and expectations across built environment actors, as well as reducing the perceived risk of adopting circular economy principles.

Riding the wave

Finally, the political landscape is also shifting. The ripples of the Blue Planet effect continue to influence a key player in the planning system: the electorate.

Planning policies and local plans have to be legitimised and justified within administrations comprised of elected members who are drawn from and represent the public. The sudden spread of interest in measures to tackle plastic waste, from the local to the international political arena, shows how powerful a change of perspective can be.

The message I took from the research was hopeful. Despite the budgetary challenges and the need to learn new skills, a number of the planners I spoke to felt that – aided by the Blue Planet effect – there would be progress on circular economy initiatives. There is some indication that this hope is not in vain: cutting the consumption of single use plastics sits alongside circular construction techniques in Glasgow’s proposed Circular Economy Route Map. Despite the challenges, there are also promising signs of progress, innovation and leadership.

Leave A Comment