by Matt Smith

7 minute readEvery local authority uses outsourcing to some degree, for services ranging from waste collection to housing estate management and beyond. They also buy in most of their goods. When they procure, they want to secure high-quality services for residents, or goods that are fit for purpose. However, some are now taking a holistic view of quality that looks beyond the direct benefits of what is procured, and requires contracts also to provide wider benefits to the local community.

One of the concerns often raised about outsourcing is that it reduces the opportunity for local service delivery to bring about wider social goods. Indeed, according to a 2019 report by the Association for Public Service Excellence (APSE), “some UK local authorities appear to have adopted an insourcing approach for reasons of social justice”, giving examples that show local authorities emphasising the use of a local supply chain and supporting apprenticeships and local skills development.

Act of commission

The Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 (“the Social Value Act”) offers a way to offer similar local benefits through public procurement, by widening the scope of the concept of “most economically advantageous tender”. Where, previously, this concept had limited public bodies to considering which tender offered the best price-quality ratio, the Social Value Act allows additional elements such as social value and environmental outcomes to be taken into account.

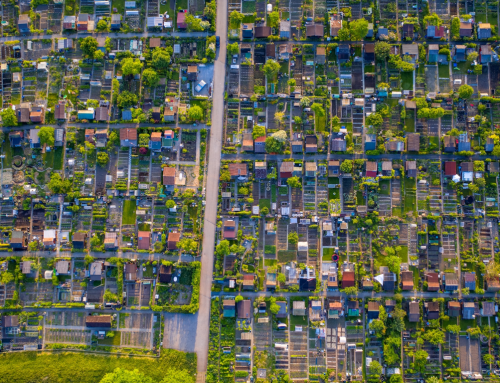

Some contracts can be worth hundreds of millions of pounds and adding a social value element has the potential to bring about long term local benefits, beyond those directly linked to the procured services or supplies. These might include job creation, supporting the local economy and improving air quality. One example of this would be for a multinational public realm contractor to offer to sub-contract a specific component of the services, such as graffiti removal, to a local business, keeping more money in the local economy.

Despite the Social Value Act having been in force for some time, authorities are not yet consistently adding a social value element to their procurements. There are two main reasons for this:

- Authorities are under financial pressures that make adding non-essential elements to the specification of goods / services to be procured (or evaluation of tenders for additional social value criteria) difficult to justify if this leads to a preference for a higher cost option.

- A lack of political will to include social value considerations within procurements, perhaps arising from a lack of appreciation of the benefits or concerns regarding additional costs.

However, these issues are being addressed as local authorities develop social value policies and strategies that set local priorities to be achieved through procurement.

Questionable value

With strategies in place, authorities can move towards implementation. However, there are three main types of challenge that they face in doing so.

- Benefits aren’t local. It is critical that authorities only give credit for additional social value where the contractor delivers benefit to the local community. If additional jobs are created many miles away, this create little social value benefit in terms of local employment or stimulating the local economy.

- Benefits aren’t additional. Social value needs to go beyond the basic requirements of the contract and create additional local benefits. If a contractor would have created a local apprenticeship position as a normal part of fulfilling the contract, or in the course of its other business, this can’t be counted as contributing social value.

- Benefits don’t offer value for money. The social value activities offered by the contractor should not cost more than the authority would wish to pay to obtain the benefit (e.g. the contractor offers open days at a waste facility to educate members of the public, but at a cost that is disproportionate to the likely number of attendees who would benefit). Similarly, the contractor’s offer should not cost more than alternative ways of securing the same benefit. For example, if a contractor offers pre-employment training for local youths for £100 per person, but the authority could have obtained the same training separately for £80 per person, then far from creating social value, the contract may impose costs on residents through requiring higher council tax payments.

Framework of values

The most effective way to overcome these challenges is to approach social value in procurement in a considered, structured way. In the remainder of this article, I set out a social value framework that Eunomia has developed with local authority clients. To begin with, let’s focus on considerations for the authority:

- Develop a social value framework that is clear, flexible and outcomes-driven. The framework needs to define clear priorities. For example, is increasing local youth employment more important to the authority than increasing spending in the local economy more generally? However, each contract will offer different opportunities, and the framework needs to allow for this. It might be reasonable to look to a long-term public realm contract to deliver improvements in local air quality, but this would not be true for a small contract to supply stationery.

- If a bidder proposes to spend the entire contract value in the local economy, at a similar cost to alternative proposals, that is achieving a benefit. However, to drive delivery of the authority’s priorities, the framework must place emphasis on specific preferences.

- Make social value an assessable element of the procurement process. If an authority wants bidders to commit to achieving social value outcomes, there needs to be a reward on offer. Assessing and scoring social value responses means that bidders who offer a robust commitment to adding such value will achieve additional points, which could be the difference between winning and losing a contract. However, the weight given to social value needs to strike a balance, so that expected differences in performance will deliver a meaningful impact on scoring relative to price, but not so significant that social value is delivered at any cost.

- Consider unintended consequences. For example, many authorities are keen to support local SMEs as potential service providers, but compared with their larger competitors such businesses are likely to have less experience of developing a social value offer and may have less scope and capability to deliver one. A focus on social value should not unintentionally disadvantage SMEs.

- Make sure that the benefits requested and offered are tangible and reportable. If a benefit isn’t measurable, or if it isn’t clear how it will be measured, how can you be sure you are gaining a real benefit?

- Evaluate in a way that distinguishes local good from the greater good. Social value is focused on creating benefit to the local area, but it is easy to end up giving undue weight to factors that have are less relevant locally. The National Themes Outcomes and Measures (TOMs) framework offers a quantitative approach to social value that could be useful in some contexts, but it takes a national perspective. For example, it places a value of £15,085.95 on creating a job for a long-term unemployed person; but this figure factors in elements such as a reduction in costs associated with welfare payments, NHS visits and police involvement. None of these costs is felt at the local level, and so the TOMs figure doesn’t accurately reflect the value of this benefit to an authority.

- Managing the promises. If a bidder has offered to create 1,000 new jobs in the local area as part of their social value commitment in the bidding phase, there needs to be a way to ensure they honour the commitment. Once the contract has commenced, the contract manager for the authority needs a mechanism to be able to enforce the commitment. This could involve developing a payment mechanism intended to adjust fees downward if the objectives are not met (as well as incentivising over-performance).

Incorporating social value in procurements is gaining momentum and local authorities that can do this successfully will be able to achieve real, local benefits through the contracts they let. Setting up a procurement process that includes a social value element allows for authorities to work in partnership with their contractors towards this common goal.

Billions of pounds are spent across the UK each year on contracted services. Councils are recognising that they can play a role – through procurement – in keeping more of the value of this spend within their local economy. As long as this does not lead to councils paying well above market rates for goods and services, then designing in social value – increasing the proportion of the spend that is focused on creating additional local jobs, improving the environment and air quality, or helping upskill young people or retrain long-term unemployed citizens – could allow contracts to leave a lasting legacy beyond the basic acquisition of goods and provision of services.

Featured image: IFA Teched (CC BY 2.0), via Flickr.

Leave A Comment